Bone China Ware in Comparison to Other Types of Porcelain

Ironically, bone china ware was originally developed as a substitute for real (or 'hard paste') porcelain in the late 1700’s, but now, especially in England, it is considered the very best you can buy.

Ironically, bone china ware was originally developed as a substitute for real (or 'hard paste') porcelain in the late 1700’s, but now, especially in England, it is considered the very best you can buy.

It is made from a special type of porcelain. Ok, let’s get some snobbery going on here. ‘Fine china’ is not the same thing as fine bone china. Bone china has some magic ingredients, and once these constituents were very a closely kept secret, and those who knew the recipe made a pot of money from their knowledge.

Porcelain is one of three types of pottery - the other two being earthenware and stoneware. Any other fancy names (majolica, delftware, jasperware etc) are just derivatives of one of these three, mainly used to describe decoration methods.

The best china has always been the thinnest and most refined.

Bone china ware is very thin and very refined, yet is the toughest of porcelains. Oh, and yes, it does contain bones.

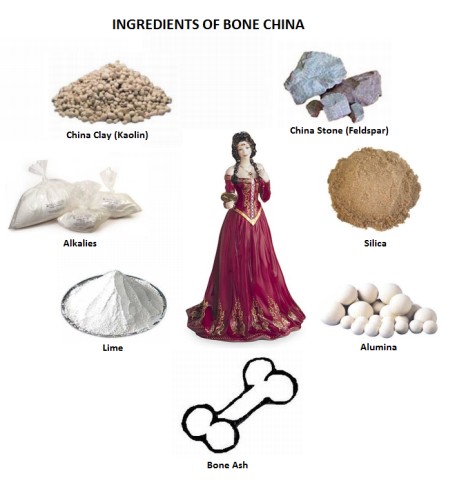

Processed bone ash makes up the biggest part of the recipe, the rest being kaolin or china clay and feldspar or China stone.

The exact recipe for bone china is still one of those magical alchemies reminiscent of Merlin himself - and the people who know what they are doing in this field - and do it well - are chemical magicians still.

I am NOT an expert in the science of bone china recipes and do not know the exact mix, but just to give you a quick ball park of the type of percentages involved is as follows:-

- 44% bone ash, 28 % china clay (kaolin), 23% china stone (feldspar), 2% silica, the remaining 3% is a mix of alumina, alkalies,and lime (burnt limestone)

The thing about these high quality porcelains (and by porcelains, I mean high temperature fired fine china mixes derived of a mix of china clay/kaolin and china stone/feldspar) is that they have to be artificially mixed and are expensive to mix and to fire.

They are expensive to mix because you can't just grab the clay body from the ground and use it. We are talking high refinement here for porcelain bodies - put together using a finely tuned recipe.

Raw clays from the ground have too many impurities, especially iron - not conducive to bone china ware!

The are expensive to fire not only because of the high temperatures needed but also because the heat of the kiln makes many more failures of slumping and 'dunting'. Many attempts at production are failures with bone china.

A pure white and translucent piece will naturally allow light to pour through the bone china ware - one of the main fascinations my father explained to me whan I was a child. This translucency is achieved, not only because of the recipe, but also due to the very high (vitreous) temperature of the kiln firing. The higher the temperature, the more expensive the firing. The high temperature allows the silica to virtually turn into glass.

All in all, it is quite a hard job for a bone china manufacturer to turn a profit, and many in the past have not been able to do so. In Germany, the early porcelain makers were sponsored by the local Nobility, not so in England where the production of porcelain has always had to be a commercial arrangement.

Production usually involves a two stage firing where the first, bisque, is without a glaze giving a translucent product and then there is a second glaze (or glost) firing at a lower temperature.

Types of porcelain

There are 3 types of porcelain – hard paste, soft-paste and bone china.

Hard-Paste Porcelain

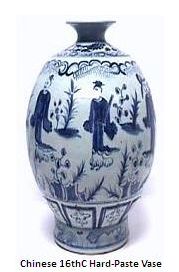

Hard-paste porcelain is what the European makers were trying to emulate when they discovered soft-paste porcelain. This ‘real’ porcelain is made from a very pure mixture of kaolin (china clay) and petuntse (petuntse is also known as feldspar or China stone) – sometimes 20% flint is added.

The resultant body is then fired at high temperatures. The clay body and the glaze melt together (vitrify) so that when hard-paste is broken, you can’t tell the body from the glaze. The colors lie on top of the glaze. Porcelain will allow bright light to pass through it.

The downfall of hard porcelain is despite its strength it chips fairly easily and is tinged naturally with blue or grey. It is fired at a much higher temperature than soft-paste porcelain and therefore is more difficult and expensive to produce.

The recipe for hard-paste porcelain is as follows: 50% china clay, 30% china stone, 20% flint. Firing: Biscuit temperature 900 C - 1000 C. Glost firing 1350 C - 1400 C.

Soft-Paste porcelain

Soft-paste porcelain was an attempt by the Europeans to copy the Chinese makers who had perfected hard-paste porcelain. However, what resulted was by no means a poor man’s substitute.

As it turned out, the inability to hold liquids unless glazed (not being fully vitrified) didn’t matter in its application for decorative art. The colors merge with the glaze to produce a wonderful silk-like effect, very appealing to the eye, and to collectors.

Soft paste porcelain contains kaolin (china clay) and petuntse (petuntse is also known as feldspar or China stone) but also includes 'frit' - a glassy substance that is a mixture of white sand, nitre, alum, salt and gypsum.

Lime and chalk were used to fuse the white clay and the frit and then fires at lower temperatures. As a result the body is granular since the ingredients do not melt together (vitrify) and therefore is weaker than bone china and liable to chip more readily.

Unlike bone china ware, and hard paste porcelain, soft-paste porcelain can be filed down. Firing temperatures: biscuit 1200 C - 1300 C. Glost 1050 C - 1150 C.

Bone China Ware

On the left is a sculpture I did in 1999 - The Fair Maiden of Astolat – reproduced in fine bone china ware by for the oldest and most renowned maker in England – Royal Worcester (Est. 1751).

For an artist, the privilege of working with such a maker is difficult to put into words. The original principles of the founder, Dr Wall, to which they can attribute their centuries of success, still run through the factory to this day.

The initial development of bone china is attributed to Josiah Spode II (son of the original Spode), who introduced it around 1799. When Josiah Spode 11 discovered bone china, he couldn’t have dreamed what a magnificent medium he was creating. Bone china is extremely hard, intensely white and will allow light to pass through it.

The standard English body basic formula remains: six parts bone ash, four parts china stone, and three and a half parts china clay. First or biscuit firing 1200 C - 1300 C. Second, Glost 1050 C - 1100 C.

return from bone china ware to homepage or alternatively back to porcelain china