European Porcelain China -

An Introduction

The history of European porcelain china is simply incredible. Fortunes, reputations and lives were won and lost. White gold was the holy grail for the Occidental people of the West whilst the inscrutable Orientals kept their secrets to themselves. This page looks at the history of European porcelain - German, French, Italian and English porcelains and how they fit into the big picture of the development of this beautiful applied art.

Of course Germany, the ever efficient technical torch-bearers were the nation who solved the ancient riddle of how the Chinese had made their precious 'white gold' of hard very (but translucent) fine porcelain. They did this in 1710 in the town of Meissen.

However, the discovery of true porcelain was made under bizarre circumstances (to our values).

A Captive Alchemist Discovers the Secret of True Chinese Porcelain and Has 'White Gold'

The King of the region captured and held captive a chemist (alchemist) and 'forced' him to find the secret.

Up until that time Europeans made soft porcelain - it didn't use the secret ingredients of feldspar rock and fine china clay, but was beautiful in it's own right and a number of priceless treasures of soft-paste porcelain still survive in museums and collections. Unlike hard true Chinese porcelain, soft-paste porcelain is porous and needs glazes to make it water-proof.

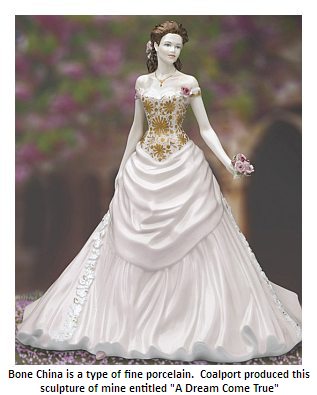

Bone china is a form of porcelain using feldspar and china clay, bit has the added ingredient of powdered animal bone. If you want to know exactly what the difference is between porcelain and bone china check out the bone china ware page

German Porcelain China

In 1710 Meissen of Saxony (later Germany) near Dresden won the European race to discover the secrets of Chinese hard-paste porcelain. Augustus II (1670-1733), King of Poland and Elector of Saxony held alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger hostage until he came up with the goods.

Subsequently, Böttger died penniless and young due to industrial poisoning. Yeah, thanks Augustus!

Meissen maintained its dominance until the defeat of Saxony during the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) when the composition and kiln technology for porcelain china, were leaked. Whoops!

It then became trendy to give princely patronage (if you were a prince, of course) to porcelain makers. You were nothing if you didn’t have your own porcelain china works.

Rapidly up to 30 factories flourished from c.1758 to around 1775. With the exception of Meissen, Nymphenburg, and Berlin, most factories closed when the novelty of porcelain waned at the end of the 18th century.

French Porcelain

Porcelain china made without the ingredient kaolin (soft-paste) was initially made in France in the late 1600’s. Several factories of significance were founded, mainly around Paris. Saint-Cloud made the earliest commercial porcelain in about 1693. Chantilly was founded in 1730. The Villeroy factory was established in 1737, later moving to Mennecy.

Vincennes was the most significant of the makers and moved to Sèvres (SW of Paris) in 1756, coming under the control of King Louis XV who granted a monopoly to the town. Sèvres began produced hard-paste in 1769. Kaolin (the secret ingredient the Chinese had been using for millenia - appropriately called 'china clay') had been discovered at Limoges a few years earlier. Lucky for them! Quickly, Limoges was established as the place where porcelain blanks or whites were made - to be sent to Sevres for decoration & glazing 200 miles away. I hope they used lots of bubble wrap, those coaches were a bit rickety.

The late 18th century saw the end of the cartel and a number of independents began to flourish in France.

Italian Porcelain

Most early European porcelain china factories produced wares and sculpture for local consumption, and generally copied Meissen and Sèvres.

Italy was the exception. Here, soft-paste porcelain had been made in Florence in the mid-16th century, and later exquisitely at Naples in the famous Royal Manufactory.

Hard-paste porcelain was made from the 1720s in Venice and at Doccia, near Florence (by the Ginori factory), in 1737.

The Naples factory of Capodimonte was first founded by Charles of Bourbon, son of the King of Spain. His wife was of the same German royal family who founded Meissen. Charles had to up-sticks and become the king of Spain, as you do, and he took his factory with him. This factory became known as "Buen Retiro" (translates as 'pleasant retreat').

Charles' son Ferdinand also had the lust for porcelain and spent much effort trying to re-create his dad's Naples factory. He succeeded and won much praise for his work.

Then in 1799 the French invaded - to takeover that part of Italy from the Spanish. The locals, fed up with the foreign rulers raised Ferdinand's precious porcelain factory to the ground. Bull in a china shop springs to mind.

Supposedly, the Ginori factory, in awe of the quality, bought the moulds and other remnants. Some say this was an just attempt to bathe in the reflected glory of the Naples Capodimonte tradition and use the pottery marks and name as a marketing aid.

Anyway, the doubt about the historical facts has meant there is no real trademark protection for the Capodimonte name and N Mark, and subsequently, when I look around the internet, there seem to be lots of different firms swearing blind THEY are the REAL Capodimonte.

Truth is, the real original Capodimonte disappeared in a puff of dust when Charles of Bourbon left Italy to become the King of Spain, only to be resurrected as a new factory near Madrid - the 'pleasant retreat'.

Capodimonte Version 2.0 under Ferdinand was breathtakingly good - and only possible to tell apart from the original Capo di Monte by the timeline of the designs. Ginori, a marvellous company on their own right, then tried, and failed, to establish the definitive Capodimonte 3.0.

Nowadays, sadly, we have Capodimonte Version "Who?".

Capodimonte is a vague Italian style, folks, not a factory anymore.

English Porcelain

English porcelain factories differed from the European makers. They were commercial ventures from the outset and, for the most part, did not enjoy the same aristocratic bankrolling. The exception to this was Rockingham of Yorkshire where the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam supported the grandiose aspirations of this high quality maker. Needless to say they didn’t last once the money ran out (see the ‘Antique bone china’ section).

In England it all started in 1567 when two potters arrived in England from Holland. They knew the secrets of tin glazing. Known as delftware in England tin-glazing took hold in locations as diverse as London, Bristol, and Liverpool throughout the 1600’s and 1700’s. Delftware was replaced in the 18th century by salt-glazed stoneware, and creamware when Staffordshire became the heart of pottery production. Soft-paste porcelain factories grew up in London – at Chelsea, Limehouse, St. James, Bow, and Vauxhall. Then Bristol became active followed by Derby, Longton Hall, Liverpool, and Lowestoft (see also 'English China’ page for more details).

A hard-paste was patented in William Cookworthy in 1768. Further experiments led to the invention of a whole new material known as bone china by Josiah Spode II c 1799.

Fine bone porcelain china is primarily an English product, but was adopted to some degree by both American and European makers. Famous names such as Lennox (American), Rosenthal (German) and Villeroy & Boch (French/German) all present bone china as an important part of their modern collections - see Antique bone china (the famous old factories).

If you have any of the above porcelain china in your hands and you would like a professional appraisal done for the purposes of identification and/or valuation, just click on the treasure chest photo near the top right of this page.

The following page is a 'must see' if you are researching fine china - for value and identification:-

Researching the identity and value of antique and vintage fine china.

I have also written a view from the inside of the making of English Bone China and I also talk about the new generation of porcelain china makers who have launched since the 1950's when bone china manufacturers were supposed to be in decline (how did they do this - what did they do different to the firms who went under?). I of course, have to have a section on Wedgwood bone china - the legend!

Further reading:

Differences between china and porcelain - www.reference.com

Return from porcelain china to homepage