- Home

- Collecting & Sculpting

- Clay Sculpture For Factory Production

Master Clay Sculpture Techniques for Factory Production

Introduction

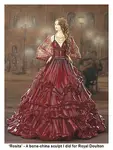

Welcome to Part 2 of the Clay Sculpting Master Series. Just a quick reminder that Part 1 focused on planning and composition, this page focuses on professional execution and structural engineering needed for master clay sculpture techniques; the constraints and methodologies required when sculpting a 'master' piece destined for industrial factory production. Part 3 looks at clay sculpture detailing and finessing, from to lace to trims, folds and foliage. It looks at how surfaces are refined, patterns and textures created, hair, faces, fabric, and flowers brought to life, and how those decisions reveal themselves in the finished collectible. The fourth guide is a run down on which tools to use for clay sculpting - basic to advanced.

The central challenge in sculpting for bone china factories is the absolute ban on internal supports. This single constraint elevates the process from art to an architectural problem that must be solved compositionally and structurally before the first mould can be taken.

Inside, we will break down the essential strategies for working without armatures for master clay sculpture techniques and follow a detailed case study of a real Compton & Woodhouse commission, tracing the 160-hour journey from initial brief to final approval.

Table of Contents: Master Clay Sculpture Techniques For Factory Production

- Building in Parts & Armature Usage

- Master Sculpture Case Study: The Double Angel Project

- Timeline Reality: What 160 Hours Means

- The Collector's Insights

- Continue To the Other Clay sculpting Pages

- In Conclusion - The Lessons From Producing Factory Commissions

- About the Author of this Clay Sculpture Guide

- Discover the Value of Your Fine China

Building in Parts & Armature Usage

The Engineering Behind Effortless Grace

When collectors admire a Royal Worcester figurine with outstretched arms, delicate fingers holding flowers, or elaborate flowing drapery, they are seeing the invisible result of structural engineering decisions made during the building phase. What appears effortless required careful planning and master clay sculpture techniques to achieve poses that survive both creation and factory production.

This section reveals why prestige bone china figurines are extraordinarily difficult to produce, and why understanding 'armature strategy' helps collectors evaluate quality.

Why Ceramic Clay Changes Everything

The critical difference: Water-based ceramic clay destined for factory casting cannot contain permanent internal armatures. Metal (or any non-clay material) inside the piece would not be able to be cut int segments by the mould makers and would also expand and contract differently than the clay - as well as restricting the pose iterations when composing the piece.

We do not use skeletal internal armatures when sculpting a production figurine piece for bone china factory production

We do not use skeletal internal armatures when sculpting a production figurine piece for bone china factory production

Unlike oil-based clays or polymer materials where wire skeletons are embedded, and a silicone mould is taken for reproduction, bone china masters must be completely "cuttable". This is because factory mould-makers slice through the piece from any direction to create production moulds. Hidden wire or rigid supports render the sculpture impossible to make slip casts from.

This constraint is why mastering bone china figurine sculpture is a rarefied skill. You must engineer stable, graceful poses without the internal skeletal support other sculptors rely on. It's architectural problem-solving disguised as art.

Strategic Part Building: The Professional Method

Although permanent armatures are forbidden by the factories, professional sculptors still build complex pieces by the use of external armatures and sometimes building parts of the sculpt separately. Solutions that translate to master clay sculpture techniques are part artistic, part logistics, part engineering solutions.

Commonly built separately, then joined:

- Extended arms (especially with dynamic gestures)

- Hands with spread or delicate fingers

- Heads and/or faces requiring extreme detail access

- Elaborate hats, hair braids or crowns

- Projecting elements made from ‘sprig moulds’ (foliage, lace, instruments, accessories)

- Trailing drapery or fabric extensions

In this example, the items that were made separately were the musical instruments, the extended arms and the stool. Note the external armature supporting the arm with the tambourine

In this example, the items that were made separately were the musical instruments, the extended arms and the stool. Note the external armature supporting the arm with the tambourine

The Process: Joining Separate Parts

- 1. Arms sculpted separately with optimal access and lighting for fine detail, then joined.

- 2. Support temporarily using cocktail sticks, wooden skewers, or removable dowels (these will be extracted before completion).

- 3. Join at medium-hard stage using score-and-slip technique when both pieces have firmed enough to self-support and not be floppy.

- 4. Blend seamlessly so joins become invisible in finished work.

- 5. Add external armature (in this case a clay rod) to support the extended arm with the tambourine.

List of Temporary Support Strategies

Without permanent armatures, professionals use supports that mainly disappear before factory handover, but not always:

- Clay posts or buttresses: Temporary columns supporting outstretched elements during building. Once the piece firms, these are usually carefully removed and the areas refined.

- Removable wooden pegs: Inserted into sockets to hold separate parts during test-fitting. Extracted when positioning is verified, holes filled and smoothed away.

- External bracing: Props joined to (not inside) vulnerable areas. Removed by the factory artists once the piece reached them safely (my primary temporary armature method).

- Cocktail stick technique: Used occasionally, especially if wrists or necks need temporary support while wet and floppy with fresh clay.

Just as construction uses temporary columns to hold up a structure before the permanent supports are set, a clay sculptor for bone china factory slip casting production uses a temporary post to support the heavy head. Once the featured fashion collar is applied and firm, it becomes the permanent support

Just as construction uses temporary columns to hold up a structure before the permanent supports are set, a clay sculptor for bone china factory slip casting production uses a temporary post to support the heavy head. Once the featured fashion collar is applied and firm, it becomes the permanent support

Sometimes, to manage the weight of heavy sections during sculpting without an internal armature, a clever master clay sculpture techniques is to place a temporary support post. This brace is made of the same clay as the rest of the piece so it can be joined securely. I want a neat looking post, which I make with a clay extruder, because my eye can then ignore it. I can then go ahead and detail the upper sections without the head falling off and ruining the face and other details.

Once the featured collar is completed, it provides a permanent structural support, allowing the temporary post to be removed.

Intelligent Pose Engineering

The best solution to structural problems is often compositional, designing poses that are inherently stable:

- Graduated projection: Elements extending outward get progressively thinner, lighter and more delicate looking. They are thicker where not visible, thinner at edges. This mirrors natural structural logic.

The edge of the cape is razor thin, giving the optical illusion of a light cape flying with movement, but the cape becomes much thicker where it is hidden, acting as an external armature to support the piece

The edge of the cape is razor thin, giving the optical illusion of a light cape flying with movement, but the cape becomes much thicker where it is hidden, acting as an external armature to support the piece

The thinness of the flying cloak is a clever optical illusion.

The thinness of the flying cloak is a clever optical illusion.

- Weight distribution: Figures with grounded stances and large dresses require less support than precarious dynamic poses. A slight bend or lean can shift centre of gravity over a stable base.

- Strategic attachment points: Arms that touch the body or rest on clothing provide natural structural support. Completely free-floating limbs are engineering challenges.

What Mould-Makers Need

Factory technicians must be able to:

- Cut through any section to create interlocking mould pieces

- Remove the master from finished moulds without damage

- Access undercuts and complex forms from multiple angles

Design considerations affecting mould-making - essential master clay sculpture techniques:

- Severe undercuts: Forms that curve back under themselves create mould removal challenges. Sometimes these require multi-part moulds or design modification.

- Fragile projections: Extremely thin elements may not survive the casting and handling process hundreds of times. Factory feedback often requests slight thickening.

- Complex assemblies: Pieces requiring multiple separately-cast parts and post-casting assembly increase production cost and failure rates. However, they are often the things that push the boundaries of perceived quality. So this aspect is always a balancing act.

Three examples of engineering challenges for the sculptor and the factory technicians

1. Victorian Snow Children

To support the double figure, we went beyond the four legs, adding a structural snow mound at the rear. Simultaneously, we addressed the gap under the front skirts, carefully sculpting the form to eliminate undercuts and allow the entire piece to be moulded in a single section

To support the double figure, we went beyond the four legs, adding a structural snow mound at the rear. Simultaneously, we addressed the gap under the front skirts, carefully sculpting the form to eliminate undercuts and allow the entire piece to be moulded in a single section

Our approach on ‘I Love Emily’ (Royal Worcester) solved both structural and practical needs. The supportive snow mound at the rear stabilises the figure, while the sculpting of the front skirts elegantly fills the gap to the ground, without undercuts, a design choice that also permitted this section of the piece to be moulded in one single, efficient section.

2. The Boy That Fell Apart

“Can I Come Too?” for Royal Worcester, posed a classic sculpting challenge

“Can I Come Too?” for Royal Worcester, posed a classic sculpting challenge

Creating 'Can I Come Too?' for Royal Worcester, for bone china production was technically demanding. The boy's form, lacking the structural support of a more usual female figurine with a long dress, relied on only the satchel and puppy. Despite strong external armatures in place, it broke into pieces during transit back to the Worcester factory, the only time this ever occurred. Thankfully, the technician was a talented artist himself and expertly put it back together without needing my involvement. So for once, with this tricky piece, my master clay sculpture techniques let me down.

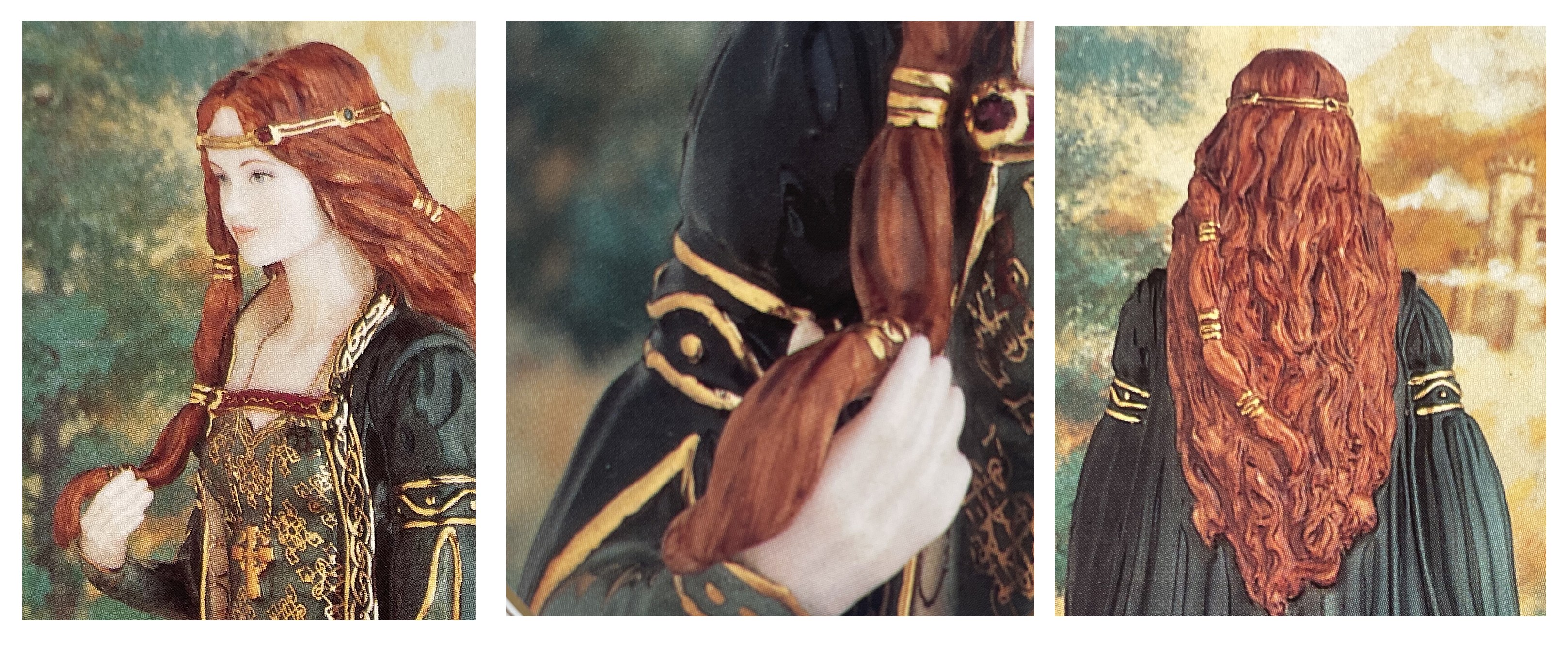

3. TARA Hair – Internal Support for the Lock of Hair

We made the "impossible" possible. This Royal Worcester figurine was the first to feature a separate lock of hair, made viable by a pioneering internal armature

We made the "impossible" possible. This Royal Worcester figurine was the first to feature a separate lock of hair, made viable by a pioneering internal armature

Sometimes you have to invent new master clay sculpture techniques. We made the "impossible" possible with Tara (Royal Worcester). We devised a two-stage internal armature solution. The long, free-flowing lock of hair required a method to prevent slumping during the wet stage and subsequent warping during drying. This was achieved by a pioneering technique (in the modern age) using an internal armature to hold the shape during sculpting process which was not removed. It was cast for moulding with the armature still inside. Worcester added a thin internal support during production for each piece. This groundbreaking technique resulted in a sold-out edition of 7,500 proving the innovation was a success. We achieved what was once thought impractical and broke the rules to make history. We pioneered the use of an internal armature to create the first bone china figurine with a separate, free-flowing lock of hair held in the hand - a feat once deemed impossible by the Staffordshire and Worcester bone china factories.

For Collectors: Reading Structural Decisions

Understanding building strategy reveals quality markers collectors can evaluate:

- Confident poses with projecting elements: Arms extended naturally, fingers sculpted realistically and delicately with detail, fabric flowing freely; these signal a sculptor who understood structural engineering.

- Awkward or bunched compositions: Unnaturally tight poses, arms pressed against body, lack of dynamic gesture often reflect pieces who couldn't solve structural challenges due to lack of quality. Cautious safety can reflect not just lack of competence but also lack of development and manufacturing budget.

- Multi-angle stability: Pieces that work visually from all viewing angles and stand solidly without appearing heavy demonstrate sophisticated structural planning during the building phase.

The Hollowing Requirement

Of course, there is is no hollowing requirement for bone china slip casting production, but those making one off pieces to subsequently fire will need to be hollowed before firing. Solid clay sections thicker than about half an inch will likely explode during firing as trapped moisture converts to steam. Professional figurine work for factory production does not need to requires no hollowing.

Amateur clay sculptures need strategic hollowing if they are to be fired. You can see the amazingly talented Philippe Faraut showing you blow by blow how to remove complex and embedded internal armatures and hollow a finely finished sculpture here: (note the relaxing music soundtrack to make the process seem less difficult).

The technique is to cut into sections, hollow out the clay, then rejoin. You cannot allow to clay to be too wet or too dry. You need to find the 'Goldilocks zone'.

The Invisible Choreography

What collectors see: graceful, effortless poses that appear to defy gravity.

What actually happened: careful choreography of separately-built parts, temporary supports extracted at precise moisture stages, strategic hollowing, and compositional engineering, all executed within the constraint of zero permanent internal armature.

Where Art Meets Engineering. Each seemingly weightless pose is a carefully engineered structure, built piece by piece to achieve its graceful balance

Where Art Meets Engineering. Each seemingly weightless pose is a carefully engineered structure, built piece by piece to achieve its graceful balance

This hidden discipline of building in parts and using only armature usage, separates prestige factory work from hobby sculpture and is one of the key master clay sculpture techniques. It's why bone china figurines from Royal Worcester, Coalport, and Royal Doulton command premiums; the technical mastery required is genuine, rare, and impossible to fake.

For sculptors: Building in parts and the use of external armatures is not a shortcut; it's professional methodology enabling poses and details impossible through single-mass construction. Master this, and you master the medium.

For collectors: That an apparently simple, complete, flowing, prestige figurine represents engineering solutions most sculptors never learn. The more you understand the constraints, the more you appreciate the achievement.

Master Sculpture Case Study - Creation for Factory Production From Start to Finish

Following a Real Commission: The Double Angel Project

The culmination of all the previous stages of master clay sculpture techniques - preparation, proportional planning, compositional verification, and structural engineering, occurs when the master sculptor begins work on a definitive factory commission. This section details the professional workflow by tracing the creation of a piece designed for Compton & Woodhouse from start to finish.

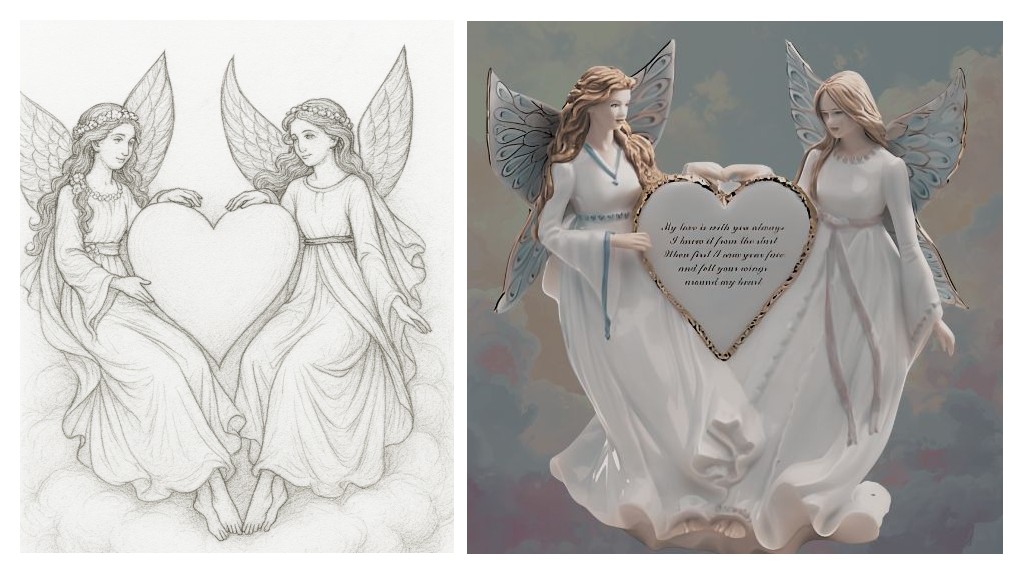

A commission for a double angel figurine for the Compton & Woodhouse Music Box collection. Left: Original Illustration. Right: The Finished Commission

A commission for a double angel figurine for the Compton & Woodhouse Music Box collection. Left: Original Illustration. Right: The Finished Commission

The Backstory

Compton & Woodhouse were exploring manufacturing certain bone china ranges in the Far East for economy. One range was their Music Box editions. They sourced a factory and had illustrators there create a concept drawing for a 'Two Angels On a Cloud' design.

The factory claimed they could handle the sculpting as well. Compton commissioned it, but the result fell far below their standards – the Far East clay modellers understood cutesy caricature and could work really fast, but not the refined elegance Compton were after. Compton rejected the sculpture and came to me to create the master sculpture properly. So the Far East factory had all the master clay sculpture techniques (probably more than me), but not the required artistic vision.

This is where real factory production standards become visible: not every sculptor understands the technical requirements, systematic approach, and refinement level that prestige bone china demands.

The Brief

Compton & Woodhouse commissioned a double angel figurine for their Music Box collection; two celestial figures in flowing robes, wings extended, capturing a moment of divine connection and love. The brief specified approximate 8-inch final height (post-firing), elegant rather than dramatic, suitable for their collector demographic seeking spiritual themes with classical refinement.

Timeline: Four weeks to deliver production-ready master

Constraints:

- No permanent internal armature (standard for bone china production)

- Wings must be created as separate slabware elements (too heavy and projecting to attach to main sculpture) using our go-to 1150 modelling clay.

- Two figures must read as unified composition, not separate sculptures placed together

- Must work from all viewing angles (360-degree shelf display)

- Mould-friendly design (factory will create production moulds from this master)

This project demonstrates every principle from previous sections: preparation, proportion, composition, building in parts; all converging in one real commission under actual deadline pressure. This is a great case study to show all the required master clay sculpture techniques.

---Week 1: Foundation & The Hook (Days 1-8)

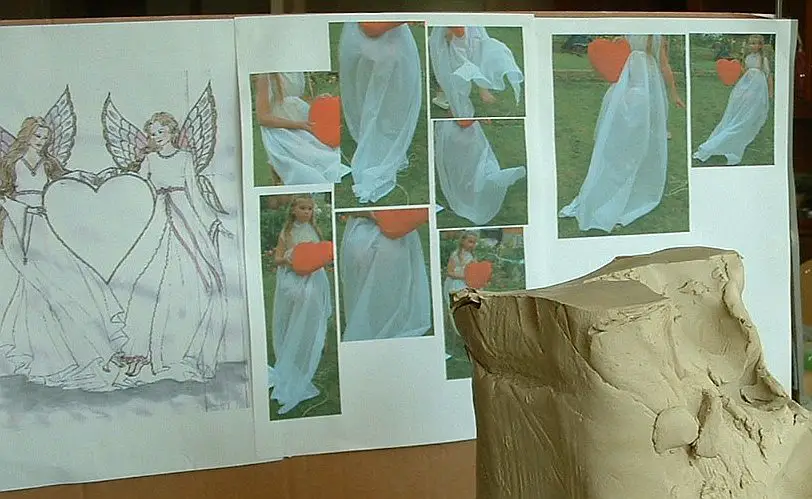

Days 1-2: Research, Fabric Studies & Reference Storyboard

Before touching clay, I gathered references: Renaissance angel paintings, wing anatomy studies, fabric drape examples, fabric reference photographs of my daughter in long flowing robes from every angle. Using the shrinkage calculation from Section 3, I determined the master must be sculpted at approximately 10 inches to fire down to the specified 8 inches after drying and firing shrinkage.

Rough compositional sketches explored how two figures could share space without crowding. The solution: subtle lean toward each other, wings angled to create negative space (though wings would be separately manufactured slabware), one figure slightly forward to establish depth.

Day 1-3 - References gathered before clay sculpting work begins

Day 1-3 - References gathered before clay sculpting work begins

Day 2-3: The Daunting Lump of Clay

I began by plonking down a mass of raw clay to get a sense of the height and scale I was working with.

You have to start somewhere

You have to start somewhere

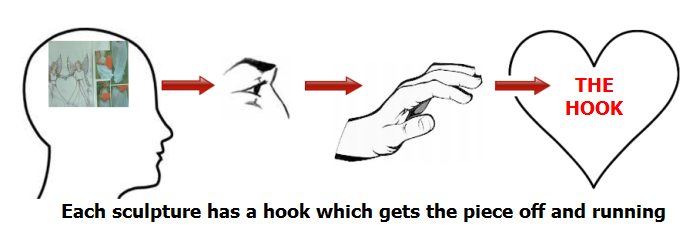

A lump of clay is intimidating; cold, wet, clumsy, slow, annoying, inert, slippery ugly mud that isn't helping at all. In the first instance, it's the enemy. I have to visualise the clay going from adversary to ally. This is where the "hook" comes in.

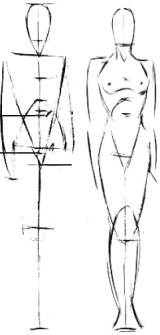

Days 3-4: Measuring, Marking & Finding the Hook

Following one of the most important of the master clay sculpture techniques - (never detail what isn't composed correctly), I began with a lump of cold clay, roughing out in my mind where both figures would be interconnected and integrated, essentially planning both the position and scale of the angels and their base.

With my anchored lump of clay on the bat, I measured and marked off heights: where the top of the head, shoulders, hips, knees would be. On this angel figurine, I knew the top of the lump was precisely where the waists of the angels would be.

How did I know? I measured (a recurring theme in my own master clay sculpture techniques).

Scale guide drawn to match the sculpture's proportions. I measure constantly, referring with dividers to my drawn scale guide (like a pin-man on paper)

Scale guide drawn to match the sculpture's proportions. I measure constantly, referring with dividers to my drawn scale guide (like a pin-man on paper)

At this stage, the piece looks crude, barely recognisable. That's correct. I'm establishing:

- Overall height and proportions

- Basic gesture and connection between figures

- Weight distribution and stability

The Hook: Making the Invisible Visible

One of the most important master clay sculpture techniques for me, not often talk about, is the 'The Hook'. The "hook" is my name for the starting point within the sculpture, the place that stops it being just a daunting lump and becomes something my imagination can work with. It's a kind of psychological trick to get me over that 'hump'.

I know where the waists of the angels are going to go; in line with the top of the central heart

I know where the waists of the angels are going to go; in line with the top of the central heart

For the two angels, the visualisation or "hook" was the central heart shape around which I would build the design. Once this heart shape was roughed out, I started feeling the shape of the dresses around each side. At this point it's all about feeling your way; making little positive visualisations.

I could now begin to see how the lovely flowing robes could be developed from the shapes in the clay either side of the heart

I could now begin to see how the lovely flowing robes could be developed from the shapes in the clay either side of the heart

It may not look like much in the photo, but for me I could suddenly see how the lovely flowing robes would develop from the shapes either side of the heart. Each sculpture has a visual hook which gets the piece going. See how I build this sculpt around the central heart. The piece was no longer just stubborn ugly clay, it had started to morph into a sculpture.

The hook is the thing that begins the conversion from enemy to ally.

Days 5-7: Building in Parts - Torsos and Heads

Using the hook and imagination, I can now "see" the design and continue the conversion. I know where things go because I've measured and marked.

Now it's time to add the parts that should be there: let's start with two female upper-body torsos.

This phase embodies the "compositional refinement" stage:

- Defining individual torsos within the shared mass

- Establishing head positions and neck angles

- Creating the subtle lean and eye-line connection

- Verifying each figure's proportions independently while maintaining unified composition

I worked the torsos off-sculpt (see Section 7) and added them either side of the heart

I worked the torsos off-sculpt (see Section 7) and added them either side of the heart

Being systematic and precise at this early stage simply paves the way for later artistic interpretation. It saves all the time-wasting of changing a model because the proportions are wrong. True creativity is always the bedfellow of precision.

In that same vein, I now placed the heads I'd been working on as separate parts.

I have worked on the heads and faces separately and now I am adding them to the heart

I have worked on the heads and faces separately and now I am adding them to the heart

These torsos and heads were by no means finished, but they were a good starting point to work on the overall composition. Both angels roughed out, forms beginning to appear. No wings, those would be made as slabware and cast completely separately, then joined in production. But proportions, faces, and gestures begin to get established.

Days 7-8: Hair Construction - The Wet Clay Sculpting Technique

Time to make the hair for the two angels. I decided one would have straight hair, the other wavy. The straight hair is more straightforward; the wavy hair required a special technique I discovered through trial and error - something I call "wet clay sculpting."

There's one technique (not that well known) which involves working much softer and more pliable clay onto your piece for certain jobs: ladies with lots of flowing hair, frills, dress folds.

I find this technique is where ceramic clay comes into its own, although it can also be done by heating up oil-based clays like plasteline.

The process:

- Soften some clay by adding extra water and soaking overnight

- Add to your sculpt where the clay has had a chance to become firmer

- Push, pull, and move the pliable clay into desired position; adjust, compose, create with the squidgy clay

Simply push and pull the pliable clay into desired position

Note the square hollow in the hair - a fixing for production to add wings. The four wings I'll make completely separately; they will never be applied to the angels during the sculpting stage and will be sculpted separately.

As the wet clay I applied for the hair gradually dries, it shrinks back to create interesting shape details. When the clay has merged back to the same consistency and these previously wet, soft additions are now workable with a tool, I can now work this into lovely delicate flowing details.

There may be some splits and cracking to attend to, but I simply press a tool into the crack to consolidate, then fill.

---Week 2: Composition Proper (Days 9-14)

Days 9-11: Composition - Now the Fun Begins

Now the essential elements are in place and definitely the right scale. It's at last time to get into composition proper.

Having done the hard grunt work, we're now allowed to get a bit arty. If you're anything like me, this is the bit you've been waiting for. It reminds me of doing interior design once the structure of the house is built. The difference is... you build the house too!

This is party time. Time for exuberance and self-expression. For example, I love doing hair. I use lots of very wet clay and fold it in with tools and brushes, then let it dry for a day or two while I work on something else.

Days 12-13: Problem Solving the Back - No Reference

In this instance, I had to figure out what was happening at the back. I wasn't sure what I was going to do here (clouds or fabric). I didn't have any references, a major problem for the part of my brain that feels naked without references. I felt a sweeping train maybe needed to go onto the back of this figurine (better than couds).

With no reference guide from C&W for the back of the sculpt, I had to do my own thing (clouds or fabric - maybe floaty cloud-like fabric

With no reference guide from C&W for the back of the sculpt, I had to do my own thing (clouds or fabric - maybe floaty cloud-like fabric

So I just improvised by rolling out a slab of clay and mucked around with it for not very long, and was reasonably pleased with what came out, so had the wisdom to stop.

Sometimes you need to know when not to over-work something. The folds on an angel's cloak out of sight on the back of a sculpture could have many different solutions, so don't sweat it too much.

The shape of a female arm (quite a complex yet specific series of planes) needs to be worked on until it's totally right, no matter how long that takes; BUT not yet. When the time comes in the detailing segment later. Meantime, the angels can have approximate arms, and the skill of positive visualisation can do the rest for now.

So this part can be fun. Who needs food or sleep? Humans can work for really long periods when in this frame of mind. This is when the donkey work is done, and it can be done quite quickly at this stage because the foundations have been laid correctly.

Composition flowing; all major elements in place but still rough

Composition flowing; all major elements in place but still rough

Day 14: The Critical Approval Checkpoint

Before any cleaning, smoothing or fine detail begins, the piece must pass the critical checkpoints of master clay sculpture techniques:

- ✓ Composition works from all viewing angles

- ✓ Proportions verified with dividers

- ✓ Weight distribution stable

- ✓ Major forms defined (but not detailed)

- ✓ Surface prepared for detail application

I had a meeting with the commissioning art director and once agreed we photographed the piece from all angles and sent images to Compton & Woodhouse's head of design for approval before proceeding. Note: there is lots of money and shareholder interest in the success of projects like this which may reach reasonably high volumes (in the millions of pounds).

This moment is crucial. Once detail begins, major compositional changes become extremely difficult. Getting approval here prevents wasted effort later.

One of the most important takeaways from this type of commission: I DID NOT START DETAILING UNTIL I KNEW I WAS NOT GOING TO CHANGE ANYTHING.

Before I put any detailing on any model, I always get the client's product development team to OK everything about the composition. If they then want to fine-tune anything about the composition after I've done detailing and it has to be redone, they get charged an extra fee. We are doing art, but we are also in business – and this is a transaction.

Week 3: Detailing Begins (Days 15-21)

The Psychological Principles of Detailing Last

So as discussed, detailing only begins in earnest once the overall composition is finalised.

The very last thing I want to happen is to carefully place lots of intricate time-consuming details only to have to scrape them all away because there's something to change within the composition.

I ask friends, colleagues, and, obviously, the product development team, I trust to give a fresh eye. Don't punch them if they say something is wrong; embrace them and their comments. Something inside was likely already telling you the same, but you weren't quite listening.

By "composition," I mean how the piece flows. Are there any awkward angles? Are the arms in the right position?

Days 15-18: Details and Facial Expressions

Following principles from Section 9 (fine detailing), the detailing work comes after every compositional and structural decision is locked in. I need to balance:

- Serenity/Elegance appropriate to celestial beings and Compton's vision and brand.

- Enough individuality of character to reward close inspection

- Detail enough to survive slip casting hundreds of times

Each face will take approximately 6-8 hours from rough volumes to refined features.

Expressions refined - serene but individual

Expressions refined - serene but individualDays 19-21: Fabric Fold Hierarchy

Fabric folds received hierarchy of detail for master clay sculpture techniques:

- Primary folds: Large sweeps establishing garment flow

- Secondary folds: Rhythmic variations adding interest

- Tertiary detail: Small creases where light and shadow enhance form, plus tiny sprig moulded detail of dozens of hearts(applied miniature hearts made by individually press moulding 1150 clay into specially made plaster of paris sprigs).

There is a great time lapse video of sculptor, Jon Burns showing how he applies folds. This is worth a watch to get an insight of the practical side of laying on and shaping clay.

Fabric folds refined with hierarchical detail from large to small

Fabric folds refined with hierarchical detail from large to smallWeek 4: Final Refinement & Handover (Days 22-23)

Days 22-23: Final Verification and Adjustments

The last days involved systematic verification:

- Rotation through all viewing angles checking for weak spots

- Structural assessment (will thinnest areas survive mould-making and casting?)

- Visual flow confirmation (any angle where composition feels confused?)

- Detail consistency (same refinement level throughout, or rushed areas visible?)

Minor adjustments made: a fabric edge softened here, a feature redefined there. Professional work is 95% right, then refined to 100% through patient final review.

I can look at the finished angel sculpt now and be critical. Unfortunately, it's too late; I got my fee and moved on.

This piece sold well for Compton & Woodhouse and unlike the Far East factory attempt at this commission, was exactly what the product development team wanted

This piece sold well for Compton & Woodhouse and unlike the Far East factory attempt at this commission, was exactly what the product development team wantedAddendum: The Wing Solution — Slabware Construction

An important principle of master clay sculpture techniques for factory production is that the wings were made as completely separate pieces from slabware (rolled-out slabs of clay). They were kept separate from the main sculpture, as they would have needed internal armature to stay attached during the sculpting process and transit—impossible for bone china production requirements.

The square hollows visible in the hair are production fixings where wings would be attached during manufacturing assembly, not during the sculpture stage.

The Handover to Factory

The finished master was carefully packed and delivered to Compton & Woodhouse's production facility. From this point, factory mould-makers would:

- Create case moulds—multi-part plaster moulds capturing every detail

- Separately create wing moulds from the slabware wing elements

- Test slip-cast pieces to verify mould quality

- Adjust if necessary (occasionally minor mould modifications needed)

- Develop production assembly process (attaching wings to main figures)

- Begin production once first test castings approved

The master itself is cut up and destroyed during mould block/case-making but the permanent reference is obtained by creating an exact replica of the original master sculpture from the first pour of the master mould for quality control throughout the production run.

Timeline Reality: What 160 Hours of Master Clay Sculpture techniques Actually Means

Total: ~160 hours over 4 weeks

This matches the professional workflow percentages of my master clay sculpture techniques:

- 25% rough massing and foundation

- 40% compositional refinement

- 35% detail and finishing

What this timeline doesn't show: The years of practice enabling each stage. A beginner attempting this same piece might need 400-600 hours and still struggle with the structural challenges and technical requirements.

What Factory Production Revealed

Once in production, this design proved:

Successful elements:

- Wing assembly system worked (separate slabware wings attached in production)

- Two-figure composition photographed well from multiple angles for catalogues

- Detail level appropriate, refined but not so delicate that production yield suffered

- Collector response positive

Learning points:

- The separate wing construction proved essential; attempting to sculpt them attached would have required prohibited internal armature

- Fabric fold hierarchy and accessory detailing made decoration intuitive for painting department

- The improvised back treatment worked successfully despite lack of reference guidance

Why This Project Demonstrates Professional Practice

This commission wasn't special because it was perfect, it was typical professional work: systematic preparation, disciplined composition, intelligent problem-solving (the separate wings solution), deadline management, and factory collaboration.

- For beginners: This reveals that professional sculpture is methodical process, not inspired magic. The crude early stages, the "enemy" lump of clay becoming an ally through the hook, the patient verification, these are normal professional experiences.

- For intermediate sculptors: The timeline shows realistic hour investment and demonstrates how principles from all previous sections integrate in actual practice. Notice particularly how wings were solved through Section 7's "building in parts" strategy.

- For collectors: Understanding the 160-hour journey behind a finished figurine explains why certain pieces command premiums. This level of care, discipline, and technical mastery can't be faked or rushed.

The Collector's Insights

When examining the finished bone china double angel in a collector's cabinet, nothing visible suggests:

- The "enemy" lump of clay that required finding a hook

- The improvised back treatment when references were unavailable

- The separately constructed wings attached during production

- The 160 hours of systematic work

What collectors do see, and respond to instinctively, is:

- Compositional strength (works from every viewing angle)

- Structural confidence (projects gracefully without appearing fragile)

- Detail hierarchy (eye drawn to faces, then flowing naturally through composition)

- Professional refinement (consistent quality throughout, no rushed or weak areas)

This is why understanding the master sculpture creation process matters for collectors: It reveals the invisible foundation of visible value.

In Conclusion - The Lessons From Producing Factory Commissions

Page Wrap-Up: From Structural Engineering to Fine DetailPage 2 has focused on the dual challenges of structural engineering (creating dynamic poses without internal armatures) and the professional workflow required to create a production-ready master sculpture for the factory. We covered the necessity of part-building, temporary supports, and the critical approval process to prevent costly changes.

The master sculpt is now complete and delivered. Attention turns to the final refinement that separates adequate work from collectible excellence, the high-level techniques used to create photo-realistic facial expressions, intricate fabric texture, and delicate accessory details.

What does the experience of a 160-hour factory commission ultimately teach us? It strips away all romantic notions of sculpting, leaving behind an uncompromising demand for structural integrity and sheer, disciplined endurance. The lessons synthesized in this guide, from the initial welding of external armature supports to the final factory production of the case study, reveals that the true job of a pro modeler is often built on steps no collector will ever see.

The Timeline Reality shows that 160 hours is not an estimate; it is the minimum entry fee for professional-grade execution. It proves that the difference between an art studio model and a factory master may just be the capacity to maintain meticulous focus over months, constantly fighting the clock while upholding material standards.

For the collector, this process delivers a singular insight: the value of a piece is directly correlated with the sculptor’s commitment to these non-negotiable structural and time-intensive phases. You are not buying clay; or even gorgeous glistening, romantic bone china, you are buying the hundreds of hours of discipline it took to bring this flawless structure to life thanks to, not only the modeler, but the artisan team at the factory too - bringing with them the knowledge passed down over centuries .

Discover the Value of Your Fine China

Inherited a china set?... Download my free 7-point checklist to instantly assess its potential value.

Inherited a china set?... Download my free 7-point checklist to instantly assess its potential value.

From the Studio

• Peter Holland Posters

• Sculpture Studio