- Home

- Collecting & Sculpting

- What is Fine China

What is Fine China? What the Term Means to

Collectors and Makers

Eaxctly what is fine china - Answering the most often asked question.

By Peter Holland, Master Ceramic Sculptor | Updated December 2025Unlike bone china and porcelain, which both have specific technical definitions, rooted in material composition and firing methods, the term “fine china” is somewhat more fluid, which is, I suspect why we get the repeated question; "Actually, what is fine china?".

Traditionally, it's used by technicians and antique experts as a catch all for high-quality vitrified porcelain and bone china. At other times, it's more of a 'market term' used by selling platforms to describe decorative ceramics that carry prestige but not necessarily vitrification - meaning it means different things to different people. In all cases it describes china regarded as 'elite'. This guide will explain all.

The one area not in dispute is that fine china is where artistry, human guile and engineering converge. It is where centuries of innovation flows to merge with modern sensibilities. Whether you have inherited your grandmother's collection or you are considering your first investment piece, understanding what truly makes china "fine" reveals a fascinating world of craftsmanship, culture, and prestige.

Table of Contents

What is fine china?- The Real Definition: A Tale of Two Standards

- The Four Pillars of Fine China (Market Definition)

- The Global Atlas of Fine China: Makers That Define the Category

- How Fine China Is Made: The Process Behind the Prestige

- Fine China vs. Porcelain vs. Bone China: Clarifying the Confusion

- Collecting Fine China: What to Look For

- Quick Reference: Fine China at a Glance

- The Modern Renaissance: Fine China Today & The Evidence

So, What is Fine China? The Real Definition: A Tale of Two Standards

This is where fine china gets fascinating, and contentious. The question; 'what is fine china?' operates on two distinct levels of understanding and both are essential.

The Technical Standard: What Experts Mean

In museums, conservation studios, and among ceramic historians like the late Henry Sandon of the Antiques Roadshow fame, fine china has a precise definition: to them, it means "fully vitrified porcelain or bone china", fired at extreme temperatures (2,300-2,600°F) to achieve a glass-like, impermeable, translucent body.

To my Worcester colleague Henry Sandon (Antiques Roadshow), 'fine china' meant something very specific.

To my Worcester colleague Henry Sandon (Antiques Roadshow), 'fine china' meant something very specific.The down to earth artisans I worked with in the studios and factory settings, simply shortened the term fine china to 'china' - and they all knew what they meant. Unlike the public who applies that word to any old cheap crockery, these technicians specifically were referring to 'vitrified wares' (bone china or porcelain).

The strict definition of fine china is rooted in material science:

- Vitrification: The clay particles fuse into a glass-like matrix

- Impermeability: The body is non-porous, does not absorb water

- Translucency: Light passes through when held up

- Resonance: Produces a clear, sustained ring when struck

Under this more general 'What is fine china?' definition, many celebrated wares do not qualify; Wedgwood's Jasperware (unvitrified stoneware), Mason's ironstone (opaque and porous), and even exquisite Minton earthenware pieces fall outside the technical boundary.

The Market Reality: What Collectors and Retailers Mean

Step outside the museum walls, and fine china can become a broader cultural and market classification; a designation earned through reputation, craftsmanship, and value rather than vitrification alone.

Across auction houses, antique dealers, and brand histories, "fine china" often encompasses elite ceramics that fail the strict material test but succeed spectacularly in artistry and prestige. Personally, I do not consider this as error necessarily, it is a shorthand, a semantic generosity reflecting admiration more than ceramic science.

That said, fine china does start with superior materials. The traditional foundations include:

- Porcelain: Made from kaolin clay and fired at extreme temperatures (2,300-2,600°F), creating that signature white, translucent, and incredibly strong body

- Bone china: England's innovation, incorporating bone ash for exceptional translucency and a warm, ivory tone

- Premium earthenware and stoneware: When crafted by prestigious makers with exceptional skill, even these "lower" materials achieve fine china status (thus, triggering the question 'What is fine china?')

Why the Ambiguity Exists

This dual meaning might be seen as evolution. As the ceramics market matured, makers like Wedgwood, Minton, and Mason elevated "lesser" materials to extraordinary heights. Their pieces commanded (and still command) premium prices, museum placement, and royal patronage. These are all markers of "fineness" in the cultural sense.

The key insight? A Meissen porcelain plate meets both standards. A Mason's ironstone platter meets only the market standard. Both might be called "fine china" depending on who is talking.

For this guide, I am acknowledging both definitions, perhaps in deference to Masons for whom I have created sculpted artwork decorated in their gorgeous colourways.

There exists a technical precision valued by experts that non-vitreous wares can embody, and the broader market usage of that reflects centuries of collecting tradition. When distinction matters, I will note whether we are discussing vitrified porcelain or elite ceramics more broadly.

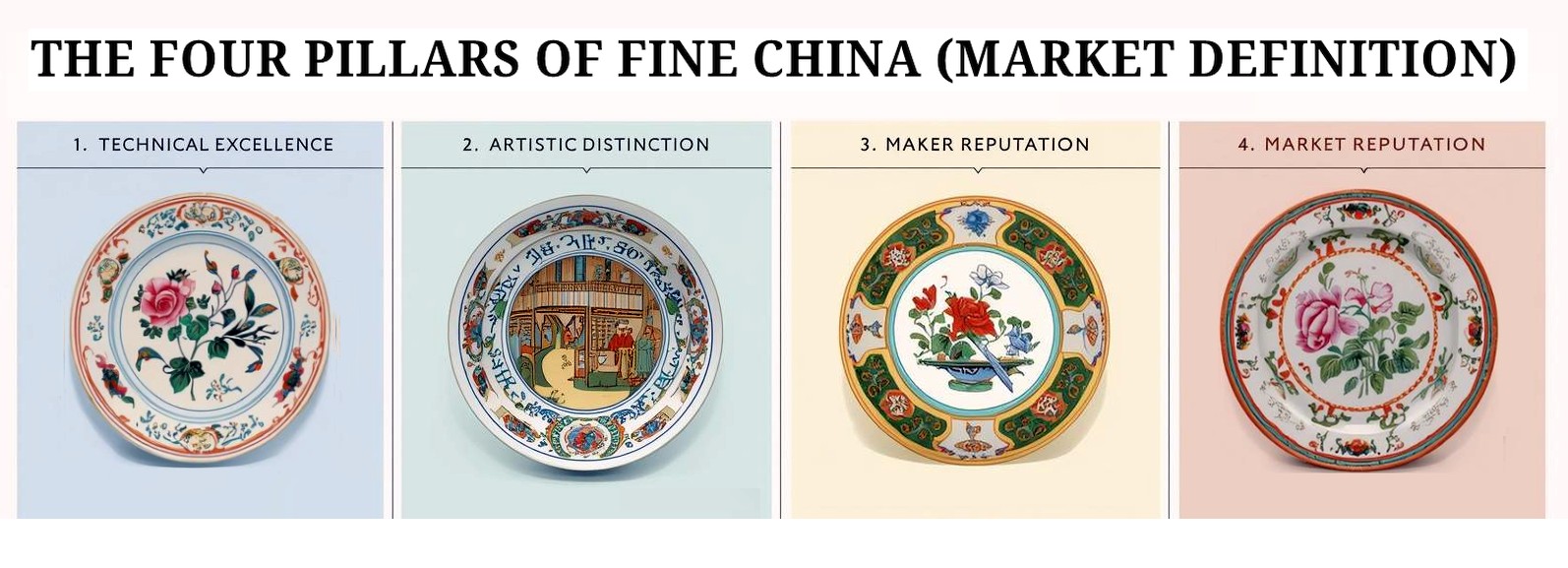

The Four Pillars of Fine China (Market Definition)

What separates fine china, in the broader market sense, from everyday ware? These four elements work in concert:

1. Technical Excellence

At minimum, fine china demonstrates mastery over difficult materials. In most cases, this means full vitrification:

- Glass-like, non-porous surface that does not absorb liquids

- Translucency (you can see light or a shadow through it when held up)

- A clear, resonant ring when gently struck

- Exceptional whiteness and uniform glaze

Note: Some pieces classified as "fine" in the market (Mason's ironstone, Wedgwood Jasperware) do not fire to full vitrification but possess high quality craftsmanship, durability and repute.

2. Artistic Distinction

The decoration matters enormously:

- Hand-painted details requiring years of training

- Complex transfer printing with multiple colour applications

- Innovative pattern design that becomes iconic (think Royal Copenhagen's Blue Fluted or Herend's Rothschild Bird)

- Precious metal accents; gold, platinum applied and fired with precision

3. Maker Reputation

Heritage and prestige are tangible assets:

- Historic houses like Meissen (founded 1710) or Royal Worcester (1751) carry centuries of royal patronage

- Consistent quality over decades or centuries

- Museum collections and exhibition history

- Awards and royal warrants

4. Market Value

The ultimate test:- what collectors will pay:

- Strong secondary market prices

- Rarity and limited editions commanding premiums

- Pattern longevity (some designs remain in production for over a century)

- Investment-grade pieces appreciating over time

The Global Atlas of Fine China: Makers That Define the Category

Fine china emerged from every major continent, each region contributing unique innovations and aesthetics.

European Masters

United Kingdom: The bone china pioneers

- Wedgwood: Innovating since 1815, perfecting Jasperware's classical beauty and Queensware's refined earthenware. Deliberately not working with vitrified china in the early years.

- Minton: Ornate bone china with museum-quality decoration

- Royal Doulton: Hand-painted figurines and dinnerware that defined 20th-century British elegance

- Mason's: Ironstone innovators whose Mandarin and Regency patterns proved durability could be fine

- Spode: Inventors of transfer printing and creators of enduring bone china patterns

Germany: Precision and artistry

- Meissen: Europe's first porcelain manufactory, where the Blue Onion pattern has been painted continuously for 300 years

- Nymphenburg: Rococo perfection and figurine mastery

- Villeroy & Boch: Bridging utility and luxury since 1748

France & Italy: Elegant sophistication

- Sèvres (France): The historic state-owned manufactory, renowned for its soft-paste porcelain and vibrant glazes, continuing the French tradition of royal luxury.

- Bernardaud (France): Limoges porcelain with contemporary collaborations (fashion houses, artists)

- Haviland (France): Thin, translucent porcelain that conquered American markets, famed for intricate floral decoration.

- Richard Ginori (Italy): A legacy dating to 1735, combining Italian artistry with technical skill, now celebrated for both classic and contemporary luxury.

Scandinavia: Minimalist modernism

- Royal Copenhagen: Underglaze cobalt painting and timeless Danish design since 1775 (known for the iconic beautiful 'Blue Fluted' pattern).

- Rörstrand (Sweden): Established in 1726, this historic house led the way in Nordic design, bridging classic forms with mid-century functionalism.

- Arabia (Finland): Mid-century modern shapes and innovative glazes, known for robust, artistic stoneware that achieved "fine" status through design excellence.

Eastern Europe: Opulent decoration

- Herend (Hungary): Hand-painted luxury since 1826, each piece signed by its artist, famous for the 'Queen Victoria' pattern.

- Imperial Porcelain Factory (Russia): From tsarist commissions to contemporary exports, retaining 18th-century opulence.

Asian Excellence

China: Where it all began

- Jingdezhen: The "porcelain capital" for over 1,000 years, still producing museum-grade pieces and high-end modern interpretations of classic forms.

- Modern luxury brands: Franz Collection and others blend tradition with contemporary global appeal, focusing on intricate sculptural porcelain.

Japan: Technical perfection

- Noritake: World-leading dinnerware since 1904, combining advanced technology with hand-finishing, highly popular in Western export markets.

- Okura Touen: Purveyor to the Japanese Imperial Household Agency, known for high-quality white porcelain and superior gold detailing.

- Narumi & Mikasa: Export powerhouses valued for quality, design, and durability, often being pioneers in high-quality Japanese bone china production.

American Innovation

United States: New World prestige

- Lenox: Official White House china maker, America's answer to European fine china, known for its ivory body and gold trim.

- Pickard: Hand-painted and gold-decorated pieces with a serious collector following; the oldest American fine china company still producing in the U.S.

- Flintridge China (California): Active mid-century, known for offering both ivory and pure white translucent bodies and a wide range of colours, a unique American response to European tradition.

How Fine China Is Made: The Process Behind the Prestige

Understanding production reveals why fine china commands premium prices:

- Material preparation: Pure kaolin clay, feldspar, and quartz are ground to micron-level consistency

- Forming: Casting, jiggering, or hand-throwing creates the shape

- First firing (bisque): 1,800-2,000°F removes moisture and prepares the surface

- Glazing: A glass-forming liquid is applied, creating the smooth, impervious surface

- Glost firing: 2,300-2,600°F vitrifies the body and melts the glaze

- Decoration: Hand-painting, transfer application, or precious metal gilding

- Decorating fire: Lower temperature (1,300-1,500°F) fixes the decoration

- Quality control: Each piece inspected; imperfections mean rejection

For the finest pieces, steps 6-7 may repeat multiple times for complex patterns. A single plate from Herend or Meissen might pass through 15-20 pairs of hands.

Fine China vs. Porcelain vs. Bone China: Clarifying the Confusion

Here's the hierarchy clearly explained, accounting for both technical and market usage:

The Technical View

- Porcelain = A vitrified ceramic material made from kaolin, feldspar, and quartz, fired above 2,300°F

- Bone china = A specific type of porcelain containing bone ash (typically 25-50%), creating exceptional translucency

- Fine china (strict definition) = Vitrified porcelain or bone china only:- the standard used by ceramic historians, technicians and conservators

The Market View

| # | Source | Item Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wedgwood Official Site | Jasperware Collections | Brand marketing uses "fine china" umbrella for all premium products, including non-vitrified Jasperware line. |

| 2 | 1stDibs Luxury Marketplace | Elite Ceramics (Mixed) | Premium marketplace uses "fine china" for any high-value ceramic tableware, regardless of technical classification. |

| 3 | Christie's Auction House | Decorative Earthenware | High-end auction houses often catalogue elite earthenware pieces as "fine china" based on maker prestige and decoration quality. |

| 4 | Replacements Ltd | Mason's Ironstone | Lists Mason's ironstone patterns under "fine china" category, though ironstone is opaque and semi-porous. |

| 5 | Antiques Atlas | Mason's Patent Ironstone | Dealer listings frequently categorize Mason's as "fine china" due to historical significance and collector demand. |

| 6 | Pottery-English.com | Minton Earthenware | Refers to "Minton fine china" including earthenware and bone china, without distinguishing vitrification. |

| 7 | Potteries Auctions | Minton Parian & Earthenware | Describes Minton's legacy as "fine china" despite including non-vitrified wares. |

| 8 | Wikipedia | Wedgwood (General) | Mentions Wedgwood as a "fine china" manufacturer, even though major product lines like Jasperware are unvitrified stoneware. |

Fine china (broad definition) = A quality designation applied to prestigious ceramics, including:

- Vitrified porcelain and bone china (always qualifies)

- Elite earthenware with exceptional decoration (Minton)

- Premium ironstone with cultural significance (Mason's)

- Celebrated stoneware from renowned makers (Wedgwood Jasperware)

The Relationship

Answering the big question "What is fine china?", in technical terms, refers to either porcelain or bone china, both of which are fired to achieve vitrification. However, in market usage, the term "fine china" often signals prestige, craftsmanship, and brand reputation as much as material composition. This can include non-vitrified wares that are culturally or historically esteemed.

Why This Matters

If you're researching a piece for insurance, conservation, or serious collecting, it's critical to determine whether the item is vitrified (glass-like, non-porous) or non-vitrified (porous, absorbent).

This affects:- Care protocols (e.g. washing, storage, restoration)

- Valuation logic (e.g. rarity, durability, market tier)

- Material classification (e.g. porcelain vs. earthenware)

For example, Wedgwood Jasperware may be considered "fine" in terms of heritage and artistry, but it is not vitrified porcelain, it’s a high-quality, unglazed stoneware requiring different handling and conservation standards.

Collecting Fine China: What to Look For

Whether you are inheriting, buying, or starting a collection:

Identifying Quality

- Check the mark: Turn pieces over and research the backstamp

- The light test: Hold up to light:- fine china shows translucency

- The ring test: Gently tap:- quality china produces a clear, sustained tone

- Examine decoration: Hand-painting shows brush strokes; quality transfers have crisp details

- Look for wear: Fine glazes resist cutlery marks better than ordinary china

Value Factors

- Completeness: Full place settings and serving pieces command premiums. A complete set from a prestigious maker is significantly more valuable than scattered individual pieces.

- Condition: Chips, cracks, and repairs dramatically reduce value. Perfect, chip-free condition is paramount for high collector value.

- Pattern rarity: Discontinued or limited-edition patterns often appreciate, especially if the pattern was highly exclusive or short-lived.

- Age and provenance: Documented history (e.g., proof the china came from a significant estate or was a special commission) adds value.

- Maker prestige: Top houses (like Meissen, Wedgwood, Herend) maintain value better than lesser-known brands, regardless of the pattern.

Quick Reference: 'What is Fine China?' at a Glance

Essential characteristics:

- Superior materials fired at high temperatures (ideally, full vitrification)

- Translucent, resonant, durable body

- Prestigious maker with documented heritage

- Artistic decoration of exceptional quality

- Strong collector and resale value

Top global makers to know:

- Europe: Meissen, Wedgwood, Royal Copenhagen, Herend, Bernardaud

- UK: Minton, Royal Doulton, Spode, Royal Worcester

- Asia: Noritake, Okura Touen, Jingdezhen

- USA: Lenox, Pickard

Key takeaway: Fine china is earned through reputation and craftsmanship, making it both an art form and a lasting investment in beauty.

The Modern Renaissance: Fine China Today

So, what is fine china to the younger generation? Well, far from being a dusty relic, fine china is experiencing renewed interest:

Millennial and Gen Z Collectors

These buyers are seeking unique, sustainable alternatives to mass-market goods. They value the durability, history, and low environmental impact of ceramics designed to last generations versus disposable dinnerware.

Mix-and-Match Trends

Modern dining styles reject uniform place settings. Collectors are combining patterns, eras, and makers for eclectic tablescapes, driving demand for high-quality vintage and antique single pieces.

Investment Focus

Consumers recognize that quality fine china holds value better than many disposable alternatives, making it a tangible, appreciating asset—an investment in beauty and history.

Sustainable Luxury

The lifecycle of fine china is inherently sustainable. It is a product that lasts generations, reducing waste compared to frequently replaced, lower-quality contemporary items.

Contemporary Collaborations

Luxury houses are actively partnering with modern designers, fashion houses (e.g., Bernardaud with Hermès, Rosenthal with Versace), and artists. This integration keeps the industry relevant and avant-garde.

Hospitality & Experiential Dining

Boutique coffee shops, farm-to-table restaurants, and independent hotels are curating vintage bone china collections to create Instagram-worthy, memorable dining experiences that convey authenticity and craftsmanship.

Brands like Bernardaud collaborate with fashion houses, while younger buyers discover vintage treasures from Royal Copenhagen and Wedgwood at estate sales.

The Evidence: Shifts Driving the China Revival

This resurgence is not merely a passing trend; it is supported by structural changes in consumer values and design culture:

The Durability and Legacy of Ceramics

The anti-disposability movement elevates ceramics. Consumers are actively searching for "heirloom quality" and "conscious consumption" in their home goods, a category perfectly defined by fine china.

The Rise of the Eclectic Table

Interior design trends, led by magazines like Architectural Digest and Vogue Living, promote styled, informal entertaining. This shifts demand away from full services toward unique, character-rich serving pieces, which are highly sought after by antique dealers.

Luxury Brand Partnerships

Strategic marketing from top houses ensures continuous visibility. Collaborations with contemporary designers and high-profile fashion names integrate porcelain into the modern luxury conversation, attracting a new demographic that values design-led objects.

Conclusion - So 'What is fine china'? The Bottom Line - What Makes China Truly Fine

“Fine china” is a term whose definition is variable. Sometimes the mention of fine china is used more or less interchangeably with porcelain or high-quality porcelain/fine whiteware. This seems to be the case in many product descriptions: ie. fine china as a high-grade porcelain. Wedgwood uses “fine bone china” as a product classification for its bone china items. But 'fine china' (without the “bone”) seems to refer to porcelain or china that does not have bone ash, or at least not significant amounts. Generally, 'fine china' is a less technically precise description, unless you an expert appraiser, then it tends to mean: high quality china/porcelain, possibly with or without vitrification, depending on manufacturer or region.

In markets/auctions, the term 'fine china' often is used loosely to include highly decorative and well regarded items made by top makers.

Whichever definition you prefer, fine china represents the apex of ceramic achievement, where geological science, artistic vision, and human skill converge. It is defined not by a single ingredient or technique, but by the cumulative effect of material excellence, maker reputation, artistic distinction, and market recognition.

When you hold a piece of fine china—whether it is a Meissen cup from 1750 or a Noritake plate from 1950, you are holding centuries of innovation, the work of skilled artisans, and a tangible connection to the rituals of dining and beauty that transcend cultures and eras.

That is what makes china fine: not just what it is made of, but what it represents and how it is made. It is the difference between a plate and a legacy.

Inherited a china set?... Download my free 7-point checklist to instantly assess its potential value.

From the Studio

• Peter Holland Posters

• Sculpture Studio