Understanding Chinese Vase Shapes

Identify Yours in Minutes

Instantly know Chinese vase shapes and what they are called. Know the value, know where they fit into history and how they were developed.

Pete's Speedy Guides - Antiquing Made Easy

Table of Contents - Chinese Vase Shapes

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The Quick-Glance Table

- Chapter 2. The Hu

- Chapter 3. Shape Developments of the Song Period (960-1279)

- Chapter 4. Shapes Introduced by the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368 AD)

- Chapter 5. The Ming Contribution (1368-1644)

- Chapter 6. The Qing Pinnacle (1644–1911)

- Chapter 7. The Broken Vase

Introduction

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

Meiping or huluping? Yen-yen or Shiliuzun? How do we know which of the Chinese vase shapes we are looking at? In minutes, with this handy guidebook, you'll know your gu from your hu.

The first thing to note is that there are only about twenty shapes in all, and each shape has its own unique backstory within Chinese culture. Each vase form is specifically named and easily recognisable, despite there being variations of shape, detailing and decoration.

The shapes became formalised over 4 dynasties lasting the best part of 1000 years under many different ruler's stewardship. It was the Song era (960-1279), which began the process in earnest and the Yuan, the Ming and Qing all made their own unique contributions until the dynastic rule was broken by revolution in 1911.

Instructions:

Each dynasty has it's own chapter, but for convenience, for those wanting to to quickly identify which category a Chinese vase shape fits into, there is a quick-glance reference table in Chapter 1.

Just look down the table, keeping an eye out for the shape of vase that most closely matches the one you are looking to identify.

When you find the one that matches, go to the relevant chapter for that shape, where the backstory for each form is explained.

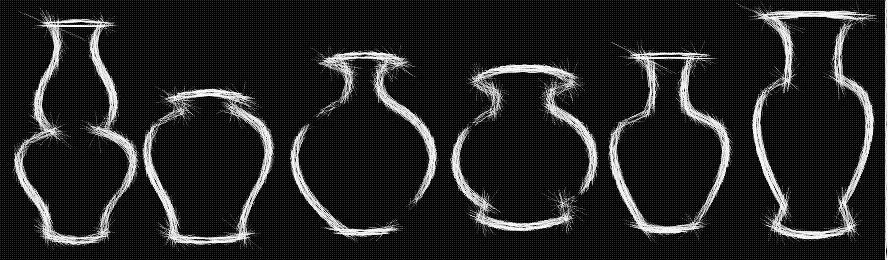

Chapter 1. At a Glance

THE QUICK-GLANCE TABLE

Meiping: also called the 'plum' vase

Yuhuchunping: also called the 'pear-shaped' vase

Huluping: also called the 'double-gourd' vase

Gu: also called the 'beaker' Vase

Suantouping: also called the 'garlic-mouth' vase

Tianqiuping: also called the 'globular' vase

Xiangtuiping: also called the 'sleeve' vase

Liuyeping: also called the 'willow leaf' vase

Bangchuiping: also called the 'rouleau' vase

Fengweizun: also called the 'phoenix-tail' or 'yen-yen' vase

Yaolingzun: also called the 'mallet-shaped' vase

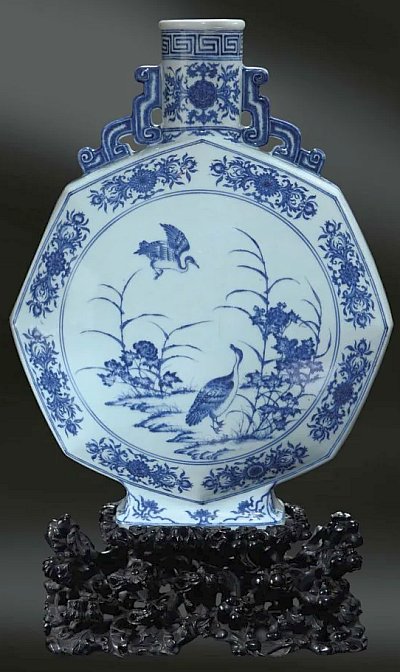

Baoyueping: also called the 'Bianhu', 'Moon Flask' or 'Pilgrim' Flask

Haitangzun: also called the 'begonia-shaped' vase

Shiliuzun: also called the 'pomegranate' vase

Zhuanxinping: also called the 'Rotating' Vase

Shuanglianping or taoping: also called the 'conjoined' or 'double' Vase

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

Chapter 2. The Hu

Over millennia, the hu form, one of the oldest of the Chinese vase shapes, evolved from being a bronze storage vessel and burial jar to a decorative porcelain art object.

The Han dynasty, 2000 years ago, gives us the first comprehensive record of the hu form, much of it excavated from graves.

The Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) was the longest running of all the dynasties. This stable society allowed for hundreds of years of ceramic technological advancement, including the development of proto-porcelain which they often applied to the hu shape.

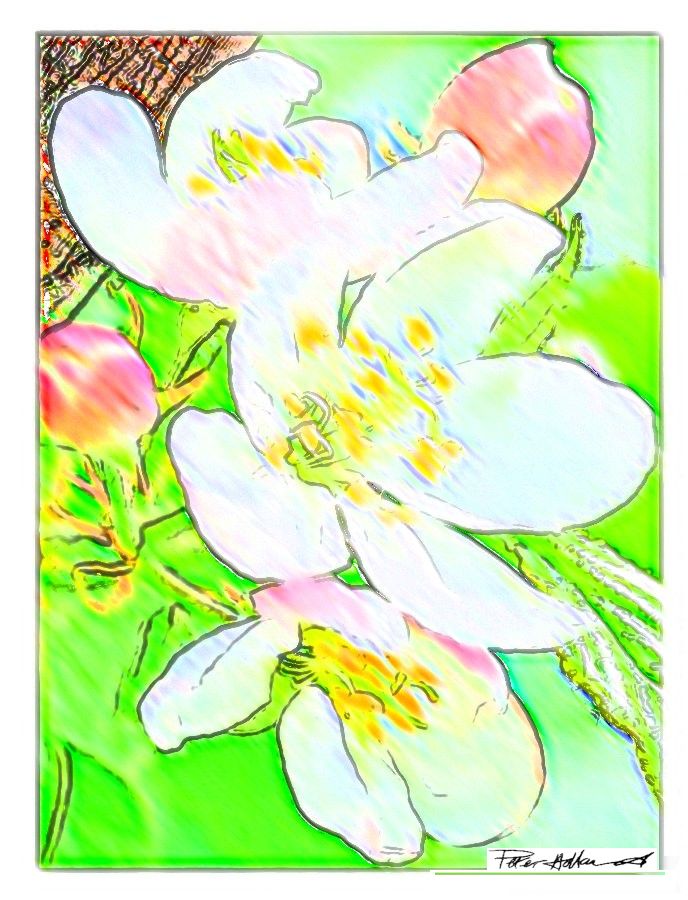

Wild Pomegranate Flower

Wild Pomegranate FlowerBaluster is a descriptive word experts use to describe the hu vessel in terms of its contours. It also applies to various other types of Chinese vase shapes that are not hu form.

The word 'baluster' just means 'gently curving', and can apply to a pillar, a balustrade and, of course, vases, jars and vessels. It comes from the Latin word "balaustium" for the wild pomegranate flower.

Later generations of Chinese ceramicists looked back to this most classic of Chinese vase shapes of antiquity and developed it in many different guises.

It was used to spectacular effect in porcelain.

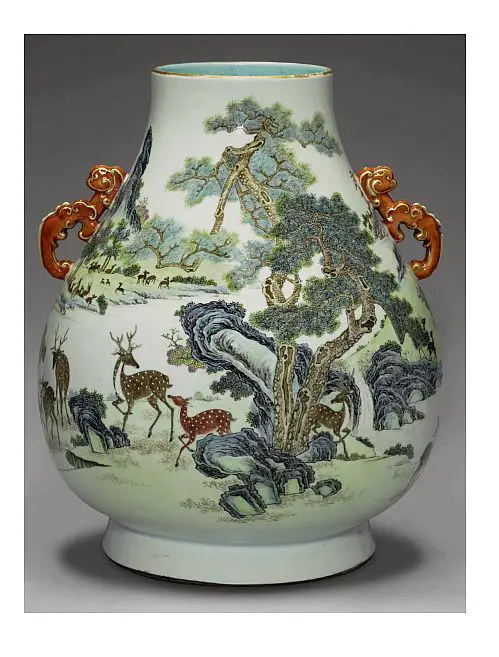

The Porcelain Niutouzun

This type of wide bodied and narrow necked porcelain hu vase (often with a pair of ornate handles) was first developed under the reign of the Qing emperor Kangxi (1661-1722) and went on to the perfected under the watchful eye of emperor Qianlong (1735-1796).

It has several different names depending upon the decoration and shape.

Vases depicting many deer within an intricate landscape are known as ‘hundred deer' vases (bailuzun) and this decoration is typically seen on a hu shape known as an ‘ox head' (niutouzun) vase.

For the emperor it would have depicted the ideal hunting scene, a favourite pastime.

In Chinese spoken word, ‘a hundred deer’ sounds the same as the popular saying which is a wish for 'bai lu' (‘boundless prosperity’) - and was a symbol of the special rank; the identifying motif for the palace.

Niutouzun are also sometimes referred to as ‘deer head' vases (lutouzun).

You may also come across this type of hu decorated in blue & white as well as other glaze techniques such as fencai famille rose.

The Hu Storage Vessel

So use of the hu form, from the humble origins as a storage vessel for wine and cereals, became a highly valuable and sought after art object.

Whatever their function, hu jars are characterised as being large, round, baluster shaped and sometimes lidded.

Don't mistake a hu for a ginger jar or temple jar - these are not categorised as classic Chinese vase shapes. They have slightly different characteristics and are generally smaller.

Lids are frequently missing on both hu and smaller jars.

The Ginger Jar

Originally designed to store spices, ginger jars vary in shape and size. They can be in hu form, but that doesn't define a ginger jar.

What defines a ginger jar is they have high shoulders and smaller mouths designed for lids. Hu often have a pair of handles whereas ginger jars don't have this feature.

Remember, ginger jars would have started life with a lid which get lost and broken, so don't mistake a large ginger jar missing its lid for hu.

The Temple Jar

The difference between ginger jars and temple jars is the shape of the lid and also their body shape . A temple jar has a characteristic pear shape and a high domed and lipped lid with a handle on top.

The ginger jar has more varied shapes which also has a flatter lid, sometimes made of wood, sometimes with a handle, sometimes without.

Also the shape of a temple jar is generally pear shaped, similar to the curves of the hu form.

The temple jar form is said by scholars to have originated in the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) and were used for religious purposes in temple ceremonies. During the 1800's, they began to become very popular made in porcelain and exported to Europe markets as purely decorative items.

People often refer to temple jars as ginger jars, not knowing the difference between them. A temple jar missing its lid is much more hu-like than a ginger jar due to its pear shape.

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

Chapter 3. Shape Developments of the Song Period (960-1279)

The stability of the Song dynasty allowed for significant advancement of ceramic techniques, ideas and designs. In between the fall of the Han and the start of the the Song there had been a significant period of unrest which stifled any major advancements.

With the Song regime restoring order, Chinese vase shapes had the opportunity to begin to take on a a new richness and diversity.

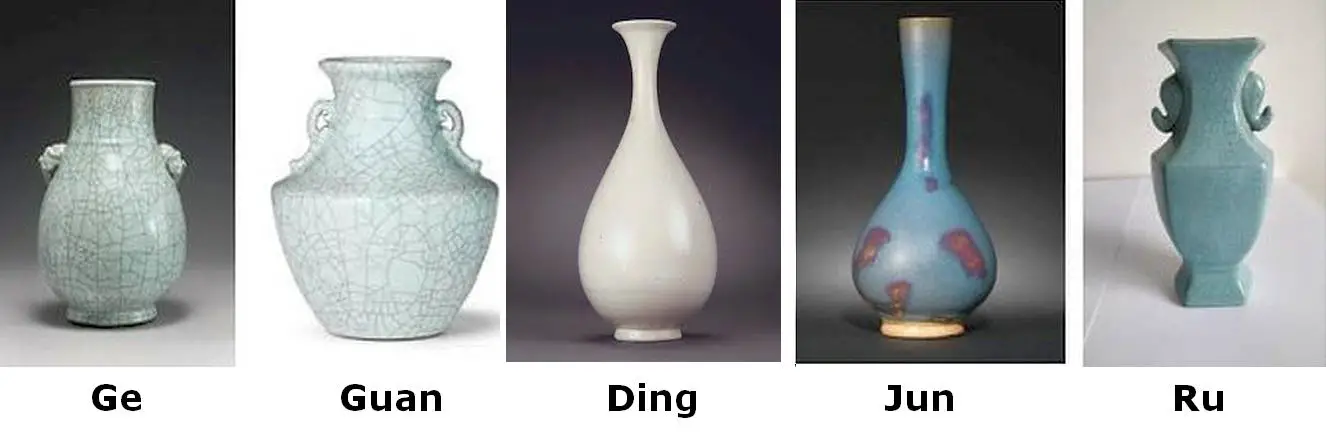

During this era, proportion, scale and technical mastery became increasingly sophisticated. Simplicity and elegance were at the core of the design ideas, particularly so in the 'famous five' kilns of the Ge, Guan, Ding, Jun and Ru.

It's interesting to note that graceful shapes from this era can be compared to the same principles as the "Golden Ratios" as written about by the Italian Renaissance scholars.

Makers began to become influenced by the beauty and cultural significance of the natural shapes of leaves, petals and fruit as well as redefining traditional shapes.

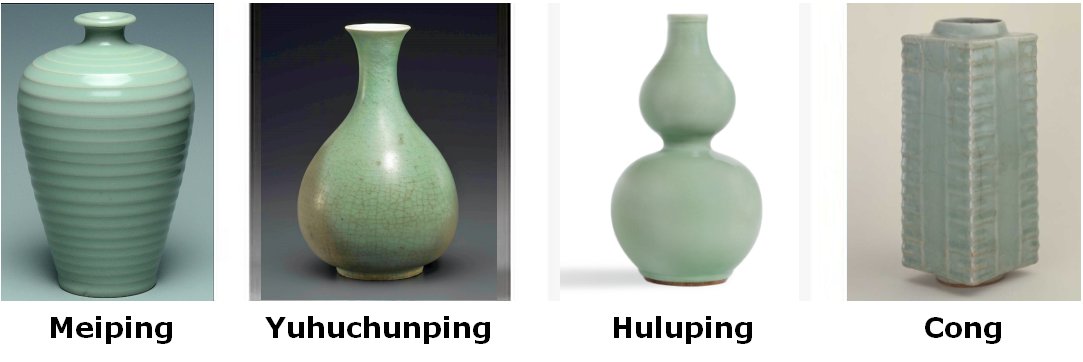

The main Chinese vase shapes which emerged in the Song era were:

- Meiping (plum)

- Yuhuchunping (pear)

- Huluping (gourd/squash)

- Cong (traditional)

Meiping: also called the 'plum' vase

'Ping' (瓶) is the word for 'vase' or 'bottle' in the Chinese language'. The same word also means 'peace', so it has a pleasant connotations. The 'mei' (梅) stands for plum. The meiping shape is said to be reminiscent of a ripe plum.

The plum shape vessel was first seen in the Tang dynasty (618–907) used for storage, burial rituals and wine transportation. The clay body was fired in what we would regard (in The West) as stoneware.

The shape then emerged as a decorative and collectible item in the Song era and was popluar through the Yuan, Ming and Qing.

The following are confirmed as genuine examples from the eras as indicated:

Images: Liveauctioneers.com

Click on any image to see the prices fetched for these items at auction. The prices range from $9,500 to $1.6 million.

In contrast, the replica below fetched £65 in the UK.

If you study the images of the meiping from the various eras, you can see how the design and decoration gradually evolved over time. It is difficult for the non-expert to know what differentiates the replica from the originals.

Although the Ming vases are of very high repute, the Qing was in fact the pinnacle of technical mastery. The replica appears to be taking the Ming style decoration as the main influence.

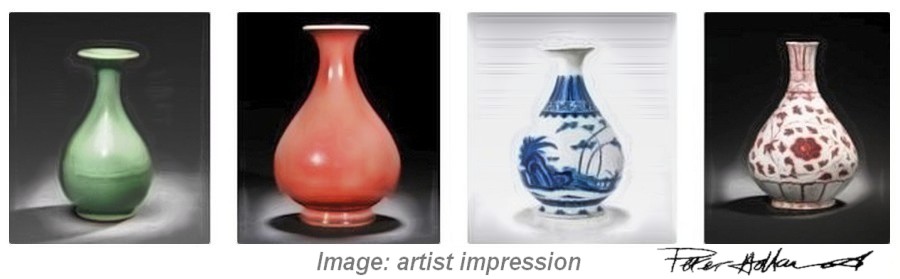

Yuhuchunping: also called the ‘pear-shaped' vase

The word yuhuchun (玉壶春) translates as 'slender wine vessel '. The word is formed from an archaic use of the words 'yu' (玉) meaning 'slender' and 'chun' (春) meaning wine. Today those words are most often read to mean 'jade' and 'the spring season' respectively.

The yuhuchunping is known to have been used in the Tang dynasty (608–917 AD) as a holy-water carrier in the religious temples of the time. It then went onto become a vessel for serving fine wine. The wine itself was called Yuhuchun, and the vase was named after the wine.

Due to its shape, the yuhuchunping has now become commonly known as the 'pear shaped vase'. In the Song dynasty, its use was developed for the first time into a decorative fine ceramic vase and was used in all the subsequent periods of production.

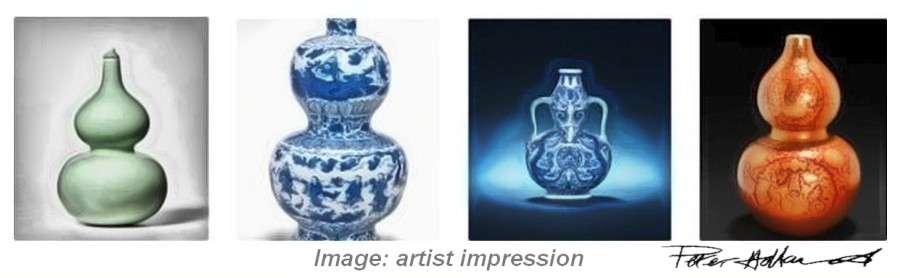

Huluping: also called the ‘double-gourd' vase

Hulu (葫芦) is the Chinese name for a gourd which is a type of squash vegetable/fruit - in the same family as cucumbers, pumpkins and melons.

There is a type of double-shaped gourd which occurs naturally and this was the inspiration for Chinese ceramic artisans in during the Song dynasty (960 to 1279) in the southern region.

In Chinese society, the gourd plant has associations with mystical powers, healing and fertility, partly because of its shape, and partly because the fruit is full of seeds. Also of course because, as a food, it contains many healthy nutrients and health giving properties.

The word hulu (葫芦) also is the same word for "protection". In addition, to make even more meaningful, the word hu (护) is also the Chinese word for blessing. The pronunciation also sounds similar to the word for happiness and high ranking success, which makes it all the more attractive.

There is also another association with the word for the number 10,000, which became associated with the wish for many decedents and thus became to mean 10,000 children.

As a result of these various positive associations, there are many different types of gourd charms in Chinese culture. It is no surprise, therefore, that the double gourd vase became such an iconic classic.

During the Song era, the double gourd shape was, of course, decorated in the palettes of the celadon. In later generations, the gourd was put to good use in the subsequent developing palettes including blue & white, millefiori, wucai and famille rose.

The Cong Form

The word cong or chong (琮) is an archaic word and refers 'a rectangular jade ritual vessel with a round mouth'. Subsequent vases made in homage to this type of vessel are also referred to as cong. It is not to be confused with the word 丛 (cong) of the same pronunciation which means 'cluster' or 'collection of'.

As a ritual vessel, the original cong shape is said to go back at least as far as Neolithic times (a period from about 10,000-2000 BC in China).

When the Southern Song rulers were forced to move south due to invasion from the north, their new location was situated near the southern kilns of Longquan. Here, the imperial court soon began to appreciate the artistry of the local ceramicists, and Chinese vase shapes began to develop anew.

The palettes were the muted but beautiful glazes of the celadon kilns. In later dynasties, the cong shape would become more colourful.

The cong continued to be a popular form throughout all the subsequent eras of Chinese ceramics.

The cong form was made throughout all the eras of Chinese ceramics. The difference in value from an original to a replica can be staggering - with the differences to a non-expert eye somewhat difficult to pick out.

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

Chapter 4. Shapes Introduced by the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368 AD)

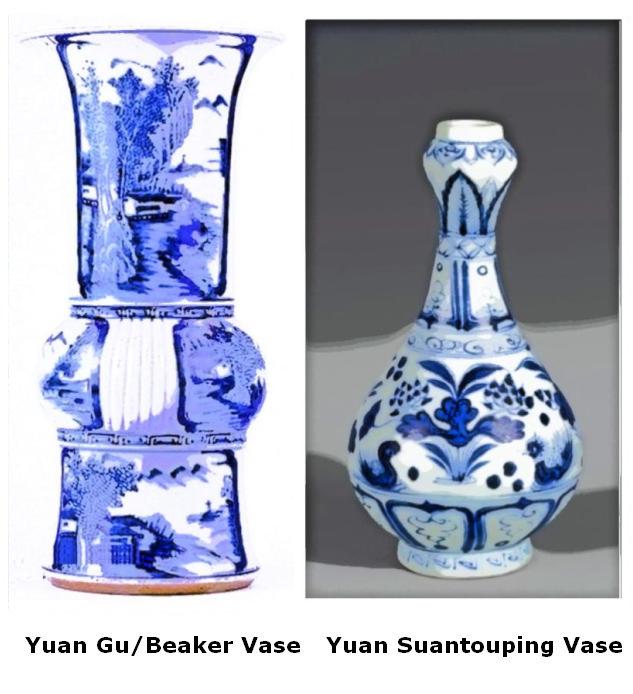

The Gu and Suantouping Chinese vase shapes are the ones which came to the fore during the Yuan dynasty.

The Gu is also known as the beaker vase or flaring vase. It has a flaring mouth, a slightly flaring foot, a stem-like body with a middle section, known as a belt or waist, which is edged top and bottom.

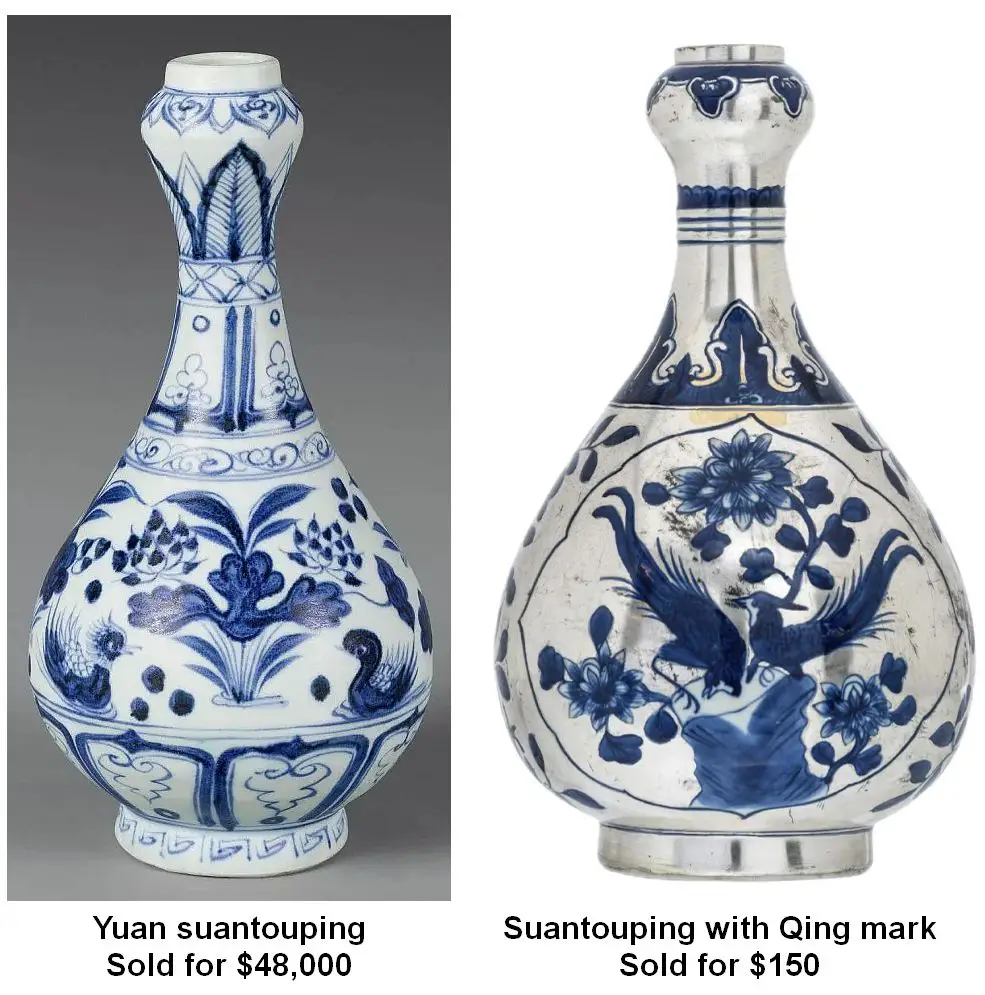

The Suantouping or ‘garlic-mouth' is a pear shaped vase, but with the addition of a garlic bulb shaped top section.

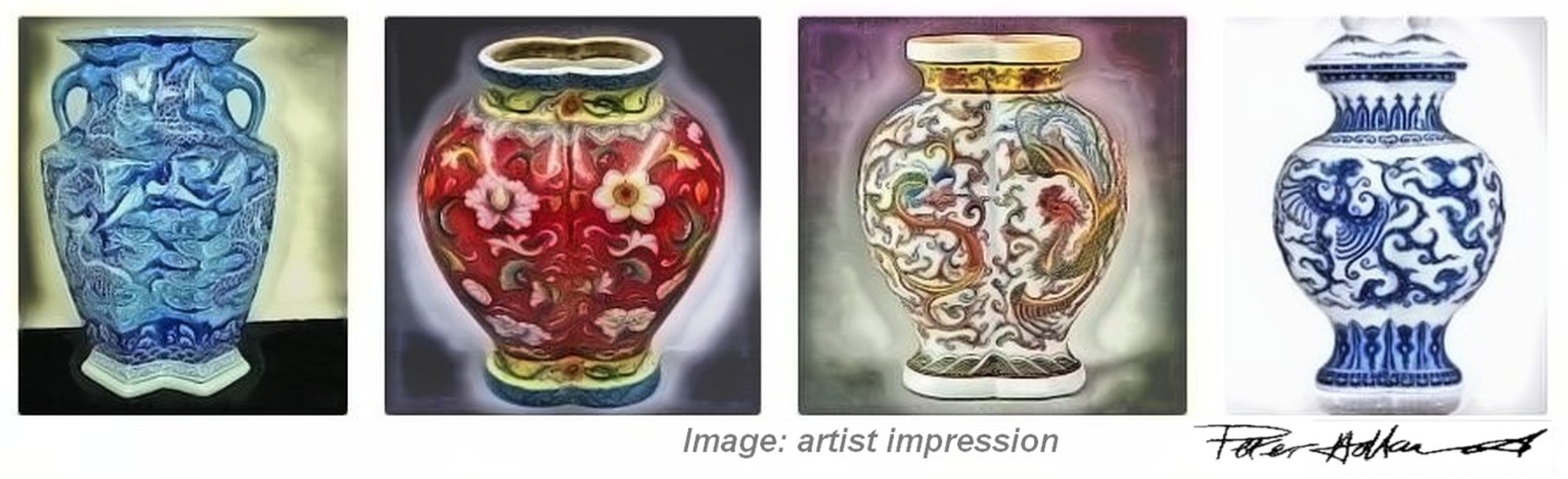

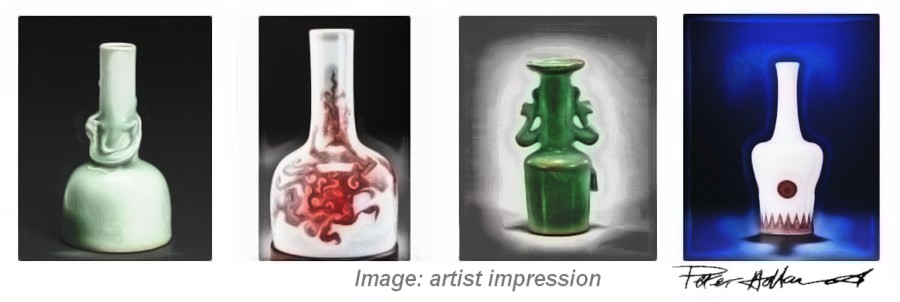

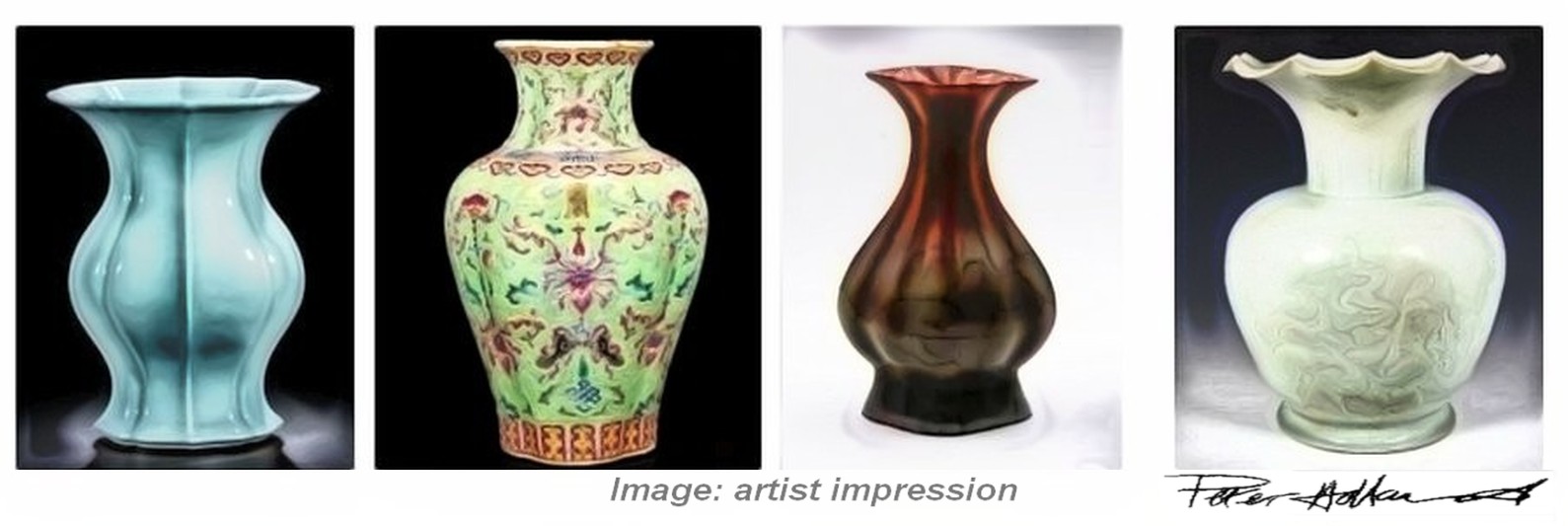

Image: artist impression

Image: artist impressionThe Yuan dynasty is the era when the first blue & white porcelain was created in China. The previous attempts at blue & white were much earlier, forgotten and unknown until found in a shipwreck and were earthenware (porous, thicker, and fired at a lower temperature.

The Yuan era is famous for China being under the brutal and forced rule of the Mongol invaders - the infamous Kublai Khan being the ruler entitled 5th 'Great Khan' of the Mongol Empire.

However, the plus side was that China was reunited as a single nation during this period, allowing for a long period of stability.

Kublai Khan

Kublai KhanAlthough with a well earned reputation for brutality, the Mongols also actively spared artisans and promoted artistry, their soldiers ordered to protect skilled workers like ceramicists.

Psychological warfare was the strategy. They carried out a "surrender or die" policy where at any hint of resistance, whole populations would be murdered, sparing only artisans, engineers and doctors.

Therefore, with a newly unified state and the emphasis placed on the maintenance and promotion of ceramic skills, it is little surprise that ceramics began to flourish during this era and more Chinese vase shapes were developed.

The gu: also called the 'beaker' or 'flaring' vase

The word Gu (顧) means to 'attend to' or 'look' or 'mind' as in a religious ceremony. The shape was around as early as the beginning of the bronze age, used in burials, rites and as a wine vessel.

Scholars generally believe (although there is disagreement) that the first true porcelains in this form began during the Yuan dynasty.

Later, the form became fashionable during the mid 1600's and again in the Qianlong reign of the Qing era (1733–1796).

In terms of looking at a gu beaker vase and seeing the difference between one worth under $200 USD and one worth $50,000, it is to do with an expert eye being able to look the vase over and seeing small but telling details in terms of wear, decoration, shape and firing characteristics and then deciding which era the item was most likely made.

It is hard for the untrained eye to do so, especially from a photograph, but you can inspect the images above to see if you see any perceivable differences.

The gu form later went onto influence a shape developed later in the Qing dynasty called the fengweizun (also called the ‘phoenix-tail’ or ‘yen-yen’ vase). Sometimes each of these Chinese vase shapes is incorrectly described as the other.

The suantouping: also called the 'garlic shaped' vase:

The word Santou (蒜头) in Chinese means literally 'garlic bulb'.

The "Garlic-bulb" mouth vase is one that first came into regular use in the creative period of the Mongol Empire's Chinese Yuan dynasty.

It takes a highly regarded and millennia old food known for its curative powers and combines this with functionality of a wine vessel, then expresses this form in technical and artistic expression that no longer needs any practical use.

Porcelain, in this era of the Yuan, became a highly regarded status symbol.

So began, during this reign, the development of the porcelain blue and white culture that proliferated to such great heights during the next dynasty of the Ming.

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

Chapter 5. The Ming Contribution (1368-1644)

In The West, the image of the 'priceless Ming vase' is etched into our collective consciousnesses. It is undoubtedly the most famous dynasty of them all and the one that if you ask someone to name a Chinese dynasty, they would most likely say "Ming".

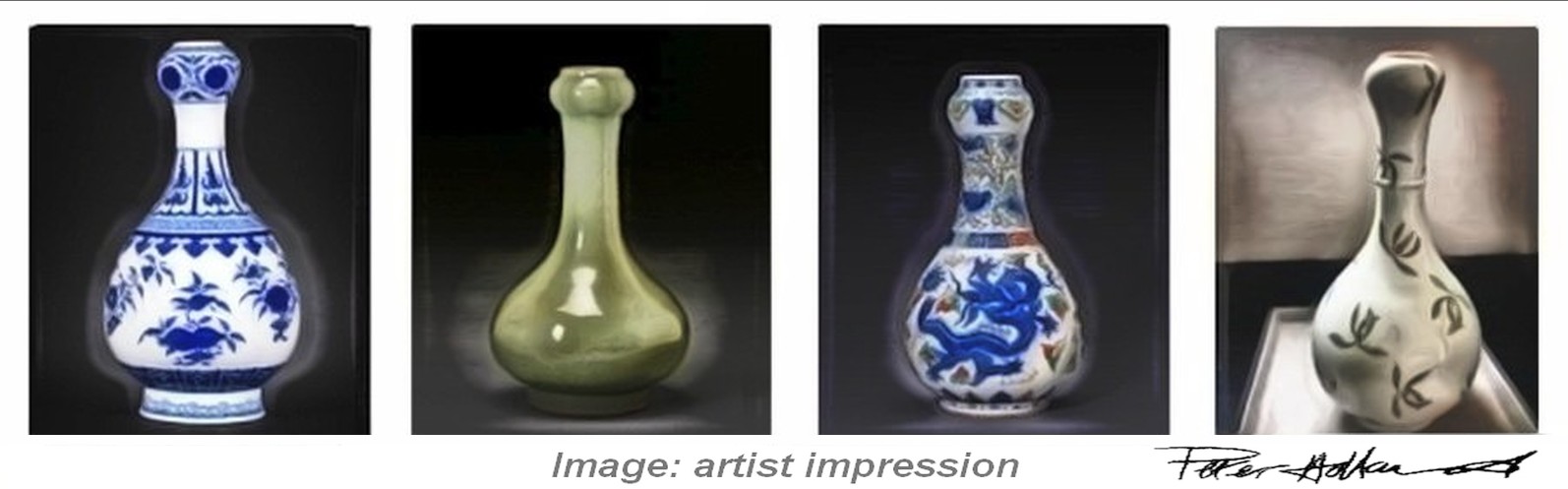

The Ming artisans used the historic Chinese vase shapes already discussed, but also invented two of their own: the Tianqiuping and the Xiangtuiping

The events which allowed for this great formative era of luxurious ceramics was that in 1367 the capital of the Mongol Yuan dynsasty, Dadu (now Beijing), was captured by the forces of the Ming leader Zhu Yuanzhang.

It was soon after, in 1368, this new dynasty took over the old long ruling empire which, in the meantime, had become somewhat corpulent and corrupt.

The new leadership lasted nearly 300 years until 1644. The development of ceramics continued to be of important cultural significance, and the continuity of reign allowed for Chinese vase shapes developments to be made.

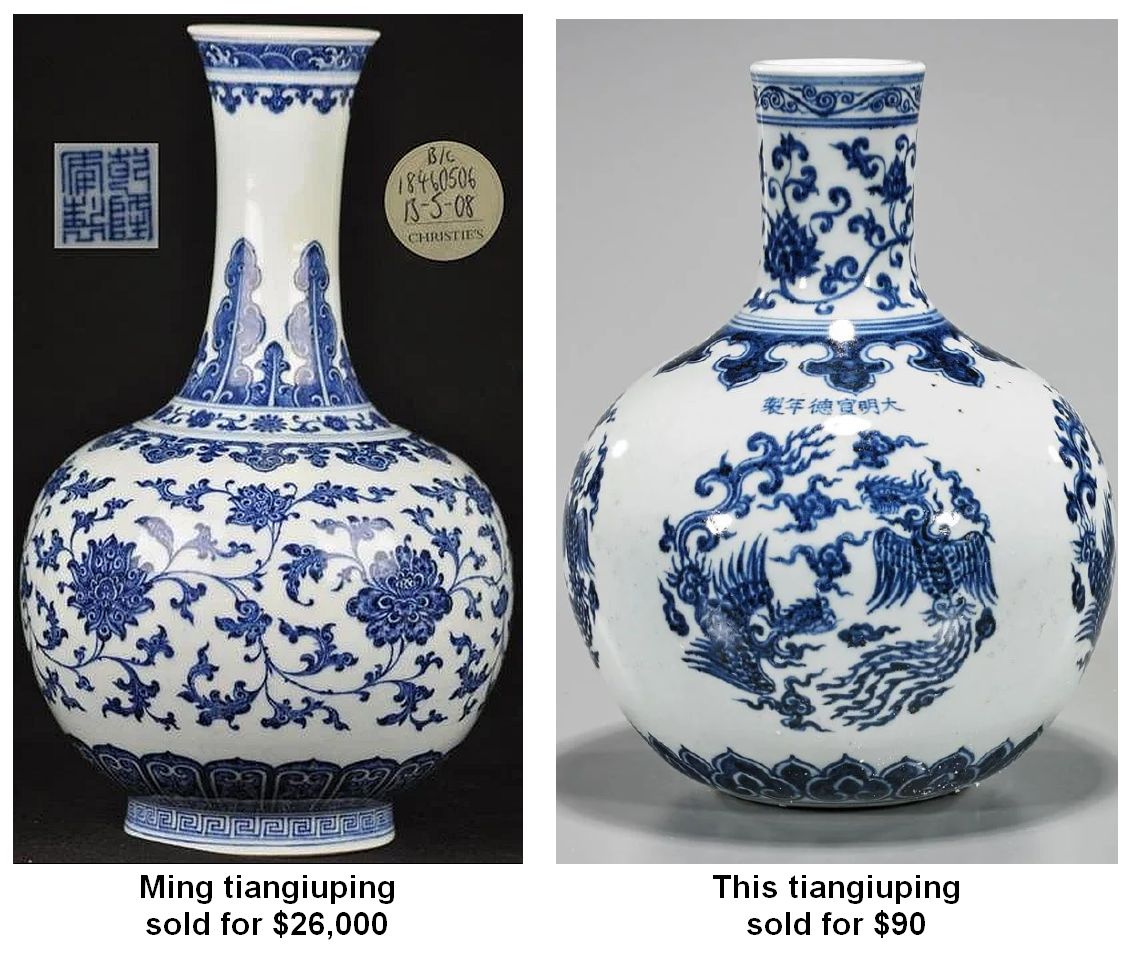

The tianqiuping: also called the 'globular' vase:

Tiangiuping (天球) means - 'Celestial ball' - again a very evocative name with much cultural significance in China.

It evokes the image of a ball falling from the sky. It's characteristics are straight neck and a round belly with a narrow neck and opening. It is said to have been imitating pottery from West Asia.

The vase on the right was marked as being made in the Xuande Emperor of the Ming dynasty who reigned from 1425 to 1435. It clearly wasn't. The one on the left appears to be a genuine Ming vase judging by the price it fetched.

This globular celestial form of vase went onto become one of the most often used in later eras for a variety of emerging decorative finishes, particularly with the subsequent Qing dynasty court.

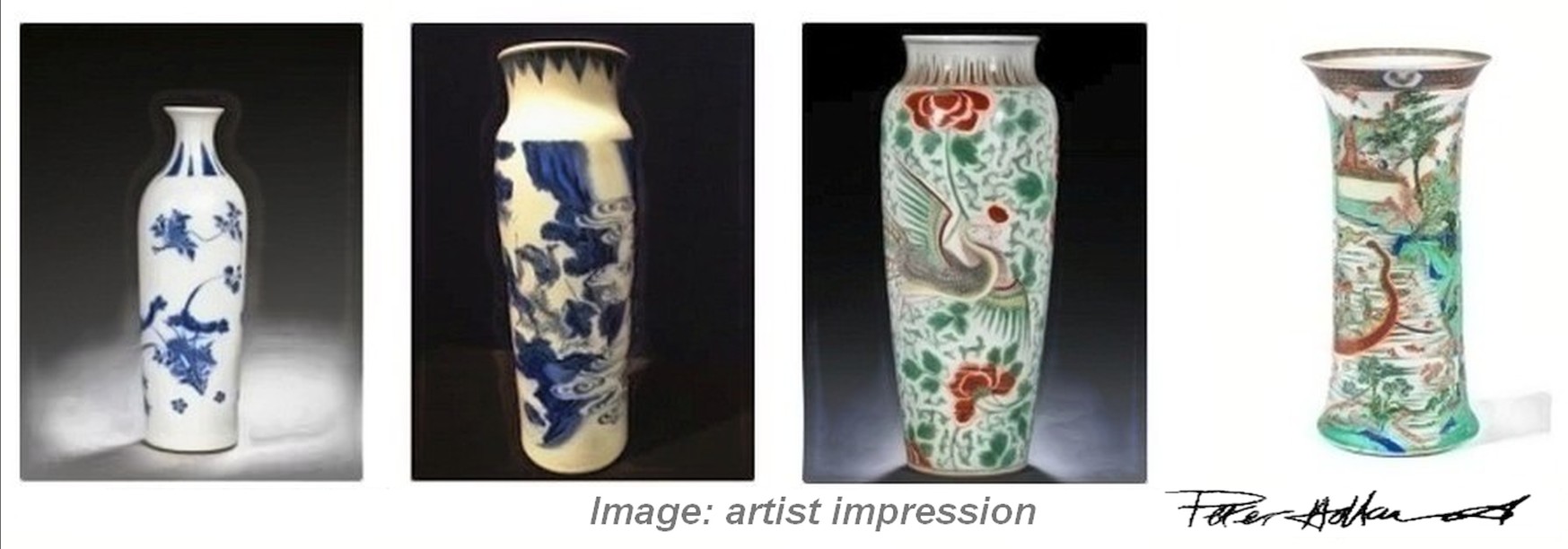

The xiangtuiping: also called the 'sleeve' or 'elephant's foot' vase:

Xiangtuiping (象腿) translates as 'elephant leg vase', although in The West, this shape became better known as the rolwagen or sleeve vase.

The main characteristic is that it's sides are more or less straight up and down like a sleeve, at least in comparison to any of the other Chinese vase shapes. This cylindrical shape then has variations of finish on a gently curving shorter neck.

Rolwagen is the Dutch word for 'rolling vehicle', a reference to a form that can be rolled, or a design which can be rolled around the vase 360 degrees. The name originated in the times when the Dutch East India Company were active in China and also very influential in Western society.

The value of sleeve rolwagens are somewhat less than other types of Ming vase - despite the fact that there are less of them around than many other of the Chinese vase shapes. So rarity with shape does not appear to increase value.

The imitation Ming xiangtuiping shown on the above right fetched a particularly low price at auction despite it being a reasonably competent replica of the real thing. Perhaps the perception of the rolwagen as a utilitarian umbrella stand doesn't help it's collectible value. Typically these vases have underglaze blue and white patterns painted continuously around the outside.

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

Chapter 6. The Qing Pinacle (1644-1911)

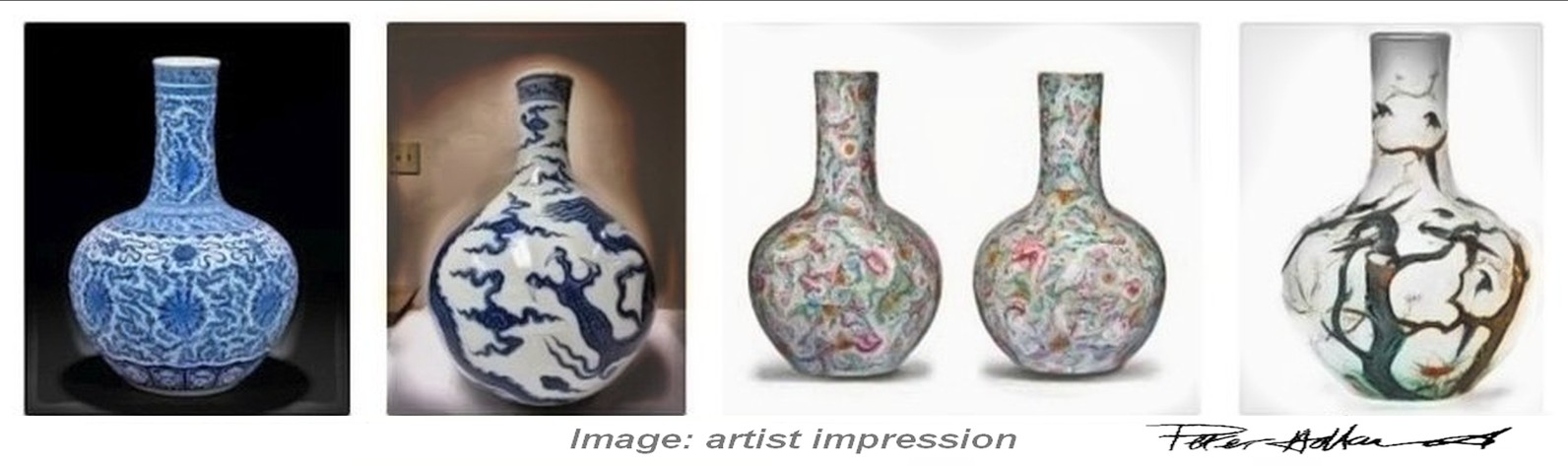

Nearly half of all the decorative Chinese vase shapes that exist were developed during this long uninterrupted Qing period - the pinnacle of ceramic success, creativity, finesse and productivity.

Background to the success

A tribe called the Manchu had overthrown the Ming dynasty by conquering the capital Beijing in 1644. They thrived by adopting Chinese ways and promoting local native Chinese (Han) administrators to rule regionally.

They also actively promoted the wisdom of Confucianism which, at the core, believes the human race is ultimately good - where wisdom, self-cultivation and virtue are learned behaviours and all that is needed to facilitate this learning is a society based on moral virtue and communal endeavour.

Given enough stability over a long enough period of time, this philosophical approach to governance was extremely conducive to the mastery of artisan skills like ceramics.

Chinese vase shapes developed during the Qing were as follows:

- Liuyeping,

- Bangchuiping,

- Fengweizun,

- Yaolingzun,

- Baoyueping,

- Haitangzun,

- Shiliuzun

- Zhuanxinping

The liuyeping: also called the 'willow leaf' or 'Guanyin' vase:

The word liuyeping (柳叶花瓶) translates as 'willow leaf vase'

The design of this vase looked to the tapering body, and slender shoulders of the willow leaf.

There is an important cultural significance to the willow. Since pre-history, the tree has been known to have powerful healing properties.

We now know the reason for this is the bark contains salicin, the same healing chemical as aspirin.

Liuyeping are also called Guanyin vases, after the Bodhisattva god Guanyin who is depicted holding one full of ambrosia (food of the gods).

The bangchuping: also called the 'rouleau' vase:

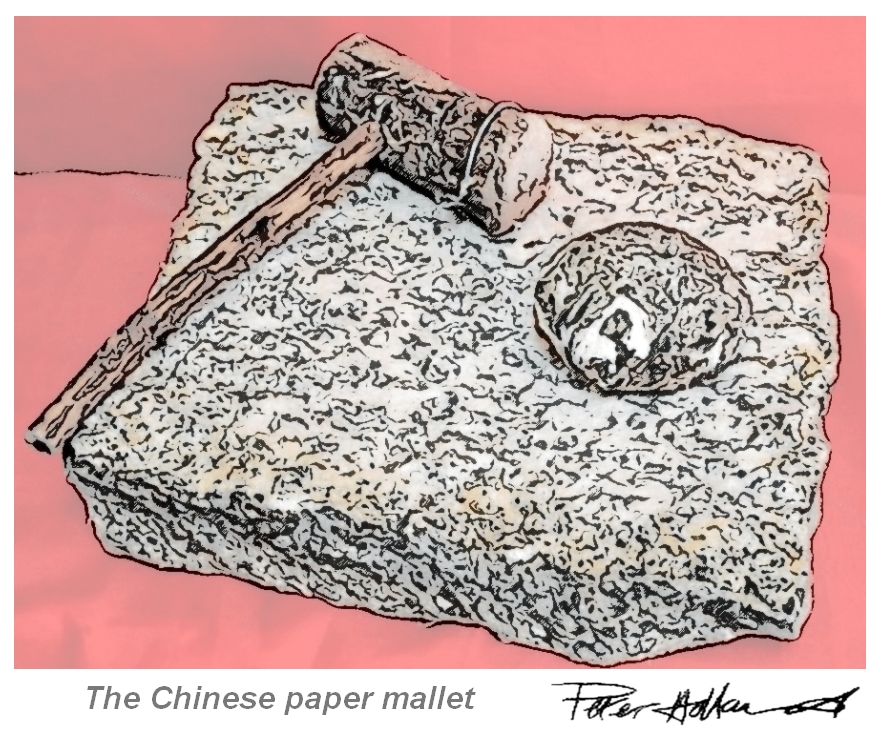

The word bangchuping (纹棒槌瓶) translates as 'grain-mallet vase'. It takes the shape of the traditional Chinese long baton for threshing grain. It was developed into a tall elegant porcelain shape built for showing off the variety of intricate decoration finishes.

The shape of the traditional Chinese grain mallet

The shape of the traditional Chinese grain malletImage: artist impression

This shape is long and cylindrical (similar to the Rolwagen - see above), with the neck being shorter than the body and the mouth with a very specific edged rim.

In Europe, this enduring and now classical bangchuping shape became popularly known by the elegant French name of 'rouleau' - meaning 'roller'. The name 'wooden club vase' may not have held the same cachet as, say, the meiping (plum) shape which was retained in the export markets.

In China, however, there are traditional poetic and proverbial references to the bangchuping grain mallet which makes it an important and revered object. It is linked with harvesting, plenty, protection and walking a straight road.

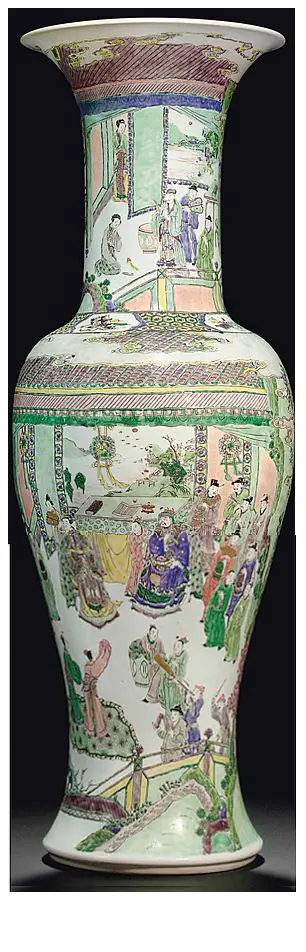

The fengweizun: also called the ‘phoenix-tail’ or ‘yen-yen’ vase

Fengweizun (鳳尾尊) literally translated means 'phoenix tail 'honouring'. This shape derived directly from the ancient shape of the gu (beaker or flaring vase). This variation of it was first developed in the Kangxi reign (1662-1722) and was often part of a garniture set (a collection of three matching pieces).

A Phoenix Tail Illustration

A Phoenix Tail IllustrationThe top of the vase flares like a trumpet, just like the gu. The gu has what is referred to as a 'belt' around the waist. In the fengweizun, the bottom ridge of the belt is dispensed with, so the form gently curves downwards in and out from the belly to the foot.

The Chinese Phoenix, is of course a purely mythical creature and was described as having a tail resembling that of a fish.

Remember, the Chinese phoenix, is similar to, but not the same as, the creature from Greek legend. The word 'feng' was originally translated from Chinese texts as 'phoenix', so the name stuck. The phoenix and the dragon are the two most popular mythical creatures in Chinese culture. The phoenix has royal connections being said to represent the empress.

So, what of the most used version if the name for this shape of vase - the 'yen-yen'? The word yen has several different culturally important connotations.

Firstly it closely resembles the Chinese yuan currency symbol '¥' (pronounced 'yen' by Chinese speakers)

¥

Secondly, the English word yen (craving) actually comes from Cantonese Chinese meaning 'hope' or 'wish' and was coined in 19th century England when everything Chinese was all the rage. It became a corruption of the English word 'yearn'.

Thirdly, in terms of the export markets, it was perhaps not so easy for European people to see the shape of the phoenix tale in the fengweizun, despite the fact that it was so named by the Chinese court because of the shape of its mouth and feet.

So, it's not surprising, therefore, an alternative name came into play for the export markets. In this case it was the word 'yen-yen' that has become popular.

This phoenix tail shape was a design of the Kangxi and during the Yongzheng and Qianlong it went somewhat out of favour, where the proportions were thought to out of balance, then by the 19th C it was back in fashion.

The yaolingzun: also called the 'mallet' vase:

The word yaolingzun (手摇铃) is literally translated as 'hand bell honouring'. The shape has a long slender neck, rounded shoulders and splayed foot, which also resembles the Chinese paper making mallet, which is why it is also sometimes called the 'mallet vase' (not to be confused with the other mallet vase already discussed, the bangchupang based on the grain mallet).

The handbell has a long tradition in China. It represents for Chinese people the high culture they have achieved as well as it's learning and science. It also represents to them the infinite wisdom of the Chinese race.

The yaolingzun is a favoured shape of Kangxi dynasty porcelain, although the kiln masters were referring back to Chinese vase shapes originally seen in the Yuan dynasty. The shape was fired during the early period of the Ming, but fell out of favour until the curious and experimental personality of Kangxi brought it back and developed it to a new height.

Records suggest that one of the uses of the yaolingzun vase was for the royal family to give to Tibetan Buddhist temples and monks as a gift and reward.

Due to its slight slim mouth, slender neck, full shoulders, and strong curves, it was prone to kiln deformation, particularly in the case of ancient wood kilns. Therefore there is a scarcity of surviving examples.

So there are two mallet vases, the yaolingzun and the bangchuping. The bangchuping shape comes from the grain mallet, but the yaolingzun was modelled after the mallet used for paper production.

The popularity of the name 'mallet vase' in the West over the yaolingzun 'handbell' name is evident in the lack of auction listings using the latter description. In Western auctions listings, only about 10% of descriptions is the name yaolingzun used.

It's worth bearing in mind that the name 'mallet vase' is used for both yaolingzun and bangchupan by Western experts and auctioneers. In China they tend to use the phrase 'paper mallet vase' (纸槌瓶) for the yaolingzun shape, whereas they differentiate the bangchupan by describing it as the 'grain mallet vase' (纹棒槌瓶).

The baoyueping or bianhu: also called the 'moon flask' or 'pilgrim' or 'flat' vase:

Baoyue ' 抱月 means "follow the moon' in Chinese. Bianhu refers to a 'wine bottle' also known as a 'pilgrim bottle'.

The design of the pilgrim bottle design is thought to have been brought to China by Buddhist pilgrims. The earliest ones weren't necessarily ceramic, they were made from a wide range of materials.

Moon Flasks in a sophisticated form of porcelain or pre-porcelain were first produced in the Ming era. Based on vessels from the Middle East, they were brought to China through traders.

The Ming examples were typically decorated in underglaze blue and later coloured enamels were used. Rare versions were in red under-glaze.

Moon flasks are a particularly active area for collectors.

In Chinese tradition, the full moon is a symbol of prosperity, peacefulness and family bonding. The moon is said to carry all human emotions within its light.

So in Chinese culture, the moon means gentleness, brightness, and 'yen' (longing). There is a specific moon festival which is an important holiday for family members to reunite and enjoy the full moon.

They will then enjoy harmony, plenty and happiness.

The haitangzun: also called the 'lobed' or 'Begonia' vase

Haitangzun: was named after the Begonia. The word “HAI TANG” (海棠) can be translated with different meanings. It can be read as “Begonia” and also “Chinese flowering crab-apple” (also referring to the fruit of this plant). There is an important cultural double meaning also; haitang is the word for the entrance hall of a Chinese home. From this association, it is synonymous with family connection, harmony and communication. It is the symbol of family distinction and honour. The word 'zun' means 'in honour of'.

Lobed petals of the Begonia or Malus Spectabilis

Lobed petals of the Begonia or Malus SpectabilisThe vase's recognisable characteristic is that it is a lobed vase - in other words it has a lobed/sectioned mouth and most often has lines running down the vase, splitting it into panels or sections.

Begonia is a common name several plants of the Chaenomeles species. The origin of the vase shape is thought by some to be that of the flower of the Malus Spectabilis. Begonia culturally represents springtime - it evokes that warm feeling of renewal and the return of flowers, the warmer weather and optimism.

This Qing cloisonne haitangzun sold recently for $55,000 by California Asian Art Auction Gallery USA, El Monte, CA, USA

This Qing cloisonne haitangzun sold recently for $55,000 by California Asian Art Auction Gallery USA, El Monte, CA, USAImage: www.caa-auction.com

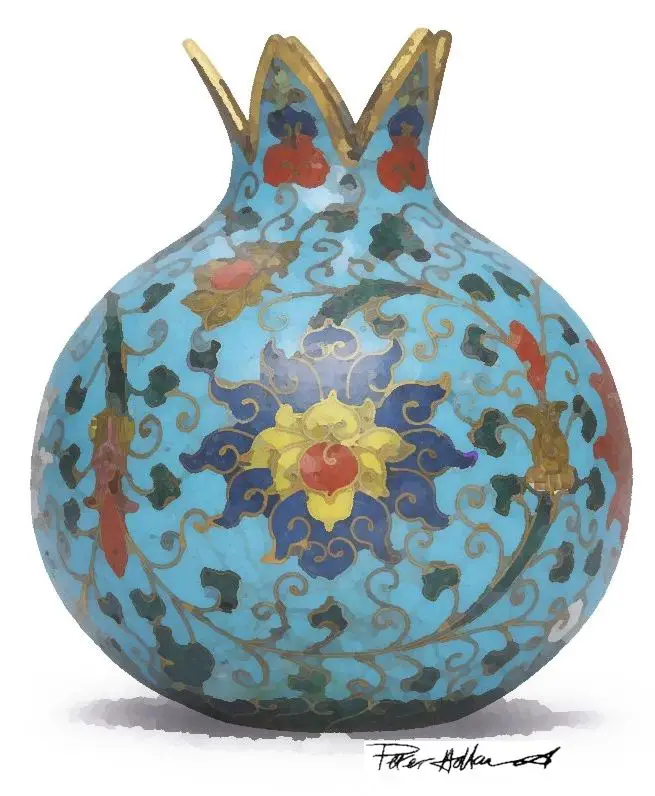

The shiliuzun: also called the 'pomegranate' vase

The word Shiliu ( 石榴 ) means pomegranate and the accompanying syllable 'zun' means to honour or respect. It is also sometimes called the 'apple zun' in China.

The characteristics of this shape are the global body and short neck. It originated in the Yongzheng period (1722 - 1735) of the Qing dynasty in the longquan kiln

.

The round shape of the pomegranate

The round shape of the pomegranateIn Chinese mythology, the three blessed fruits are the pomegranate, the peach and the citrus fruits (the 'sanduo', or '3 abundances').

The pomegranate is the symbol of abundance of descendants, fertility and a charmed future.

It was only a matter of time before a vase shape was developed to pay homage to this highly regarded fruit. It was the cultural boom of the Qing dynasty that allowed this to happen.

Image: artist impression of Chinese pomegranate painting

Image: artist impression of Chinese pomegranate paintingIt was the prosperity of Buddhism in China that started the promotion of the popularity of plant patterns in art, and at that point the pomegranate was absorbed into Buddhist decorative arts

A blue & white shiliuzun Yongzheng period - Image: artist impression

A blue & white shiliuzun Yongzheng period - Image: artist impressionRecent medical studies have shown there to be antibacterial, anti-parasitic, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and anti-allergic properties within the pomegranate. This is where mythology meets science.

An early Qing shiliuzun cloisonne fetched $105,000 at Christies Hong Kong -

An early Qing shiliuzun cloisonne fetched $105,000 at Christies Hong Kong - Image: artist impression

The zhuanxinping: also called the 'rotating' vase

Four examples of the zhuanxinping type vase

Four examples of the zhuanxinping type vaseZhuanxinping (转新平) can be translated as 'new turning vase', which explains this shape pretty well. In the mid 1700's during the Qianlong reign of the Qing dynasty, at the very height of porcelain artistry in China, the idea of creating one vase inside the other was born.

What became known as the Zhuanxin vase was the product of the extremely prosperous court life in Qianlong reign (1736–1795) of the Qing dynasty, where the Emperor Qianlong was besotted with porcelain and wanted to achieve creative ideas never been seen before.

The idea was to have a smaller rotating vase inside a larger ornate reticulated vase.

On the smaller vase, revealed through the reticulation, was exquisite hidden artwork.

This idea was outrageous in concept, extraordinarily difficult to make, not to mention being almost impossible to fire successfully.

So it was that, under the patronage and encouragement of Qianlong himself, the concept of the rotating or revolving vase was painstakingly developed by Tang Ying (1682-1756), the supervisor of the Royal Kiln Factory, together with his assistant Laoge.

It wasn't until the establishment of the Palace Museum in the 19th year of the Republic of China (1930) that these vases were first shown to the public. Before this they were locked in the Forbidden Garden of the Qing palace.

The Zhuanxinping became the highest peak of "Tang Kiln" porcelain, which in turn, was the golden era of Chinese fine ceramics.

The vase shown above is a genuine one from the Tang Ying kiln during the Qianlong period. If is extremely luxurious and breathtaking. It fully embodies the highest achievements of the official kiln and the porcelain production processes of the Qianlong period.

So these vases are extremely rare and precious there are very few in existence and even fewer ever available on market. When they do come up for sale, they tend to be sold by Sotheby's Hong Kong and bought by state museums like the Beijing Capital Museum.

At the time of manufacture, the cost of making revolving vases in the Qianlong imperial kiln was huge. Only one in a hundred would survive the making process. Obviously, the ones that did survive were exclusively for the palace and for the pleasure of the emperor.

The shuanglianping or taoping: also called the 'conjoined' or 'double' vase

Shuānglián (双莲坪) simply means 'double'

Taoping (桃瓶) translates as 'peach pottery' referring to vases that have the appearance of being in two distinct halves.

Again, like the revolving vase, this idea was a development of the Qianlong court when porcelain making was at its height and looking to further the production of ceramics as a means artistic perfection.

These vases are also rare and genuine Qianlong examples come up infrequently at auction.

This small 19th century conjoined taoping vase was estimated to sell for around $300-$400 USD. However, such is the interest in Chinese porcelain that it was sold to a Chinese bidder by Michaan Auctions in Alameda in 2016 for $20,000.

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

Chapter 7. The Broken Vase

Ceramic quality and design came to a height under the 60 year rule of Emperor Qianlong of the Qing dynasty. He died in 1799.

Following this height, ceramic quality and continuity of output was on the way down. The bubble had burst, the vase was broken.

The next Jiangqing period witnessed a decrease in national strength and was unable to further develop the technology that went before. New thinking and innovations on Chinese vase shapes were never made again.

By the next ruler, Tongzhi (1862-1874), the quality of the imperial kilns were not markedly different from those in the rest of the country. Through the final reigns of Guangxu and Xuantong a smattering of porcelain vases were made, but the great days of the Ming and Qing Empires were over.

Finally, in 1911, the immensely long dynastic era in China came to an abrupt end and the glory days of fine china making was gone.

The influence and reputation of Chinese porcelain continued in the West unabated in the 20th century as the European and American makers took up the reigns of fine porcelain production. Many great companies emerged from the flames of the Chinese decline, so much so that the average person in Britain, Europe and America developed such a collectors bug as to make companies like Meissen, Villeroy & Boch, Royal Worcester, Wedgwood, Coalport, Royal Doulton, and Lenox household names.

English bone china and European porcelain became the stamp of the aspiring working and middle classes.

This collectors bug for fine china continued for the most part right the way through the 20th century, only to fail when the generation that cared about fine china ceased to be. By the early 21st century, with only a few exceptions, most of the great European and American makers were themselves extinct.

If you like the content of this post and want to have your own copy for future reference (without ads), download the full e-book for only $9.99

For further reading go to this website on Chinese vase shapes

Return from Chinese vase shapes to the main hub page explaining how to read Chinese pottery marks or alternatively go back to the home page

Inherited a china set?... Download my free 7-point checklist to instantly assess its potential value.

From the Studio

• Peter Holland Posters

• Sculpture Studio